‘Surprise and relief’ from homeless patients: ‘This works for me’

‘Surprise and relief’ from homeless patients: ‘This works for me’

Doctors report ‘fascinating and counterintuitive’ results delivering healthcare to hard-to-reach population via telehealth

Alvin Powell

Harvard Staff Writer

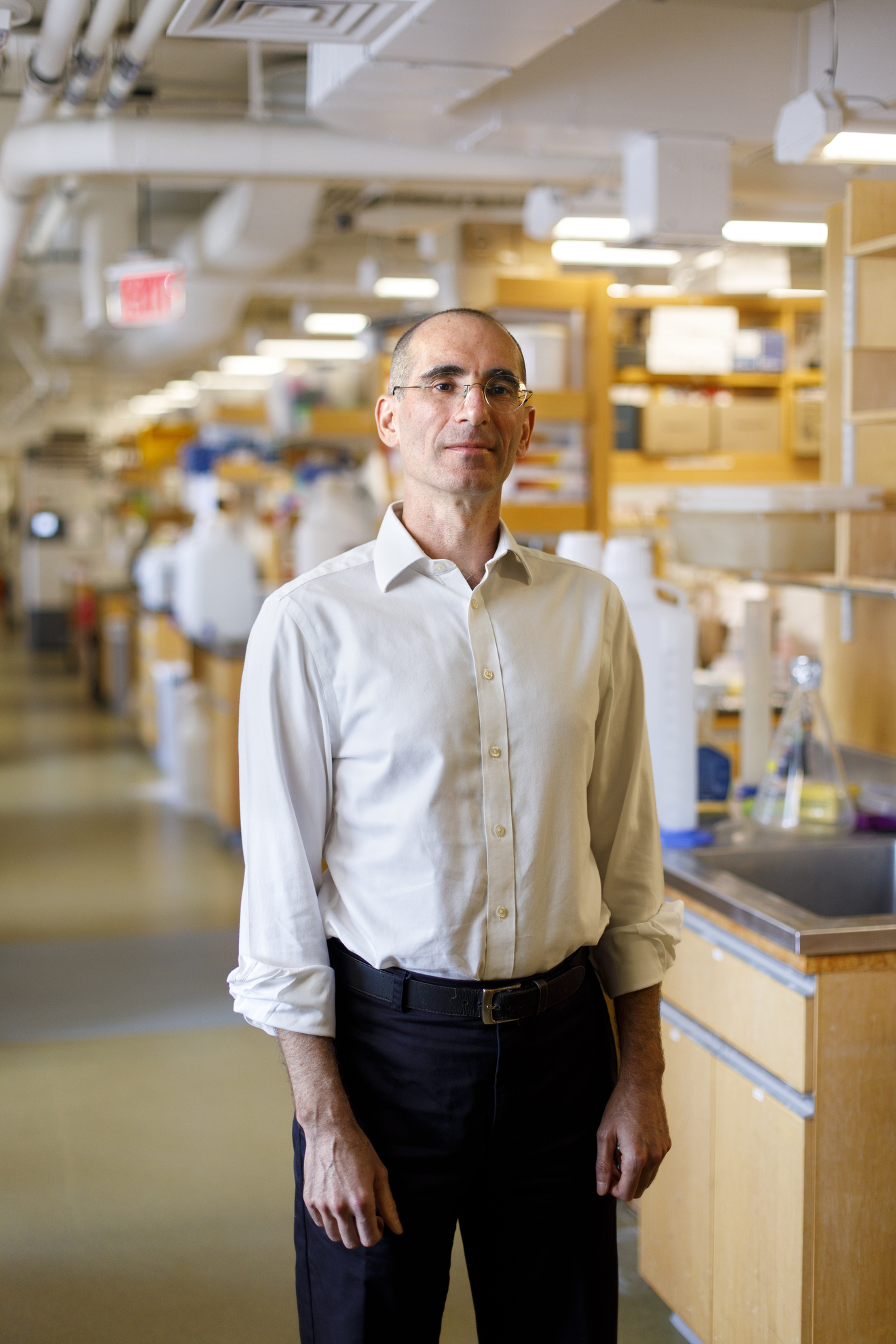

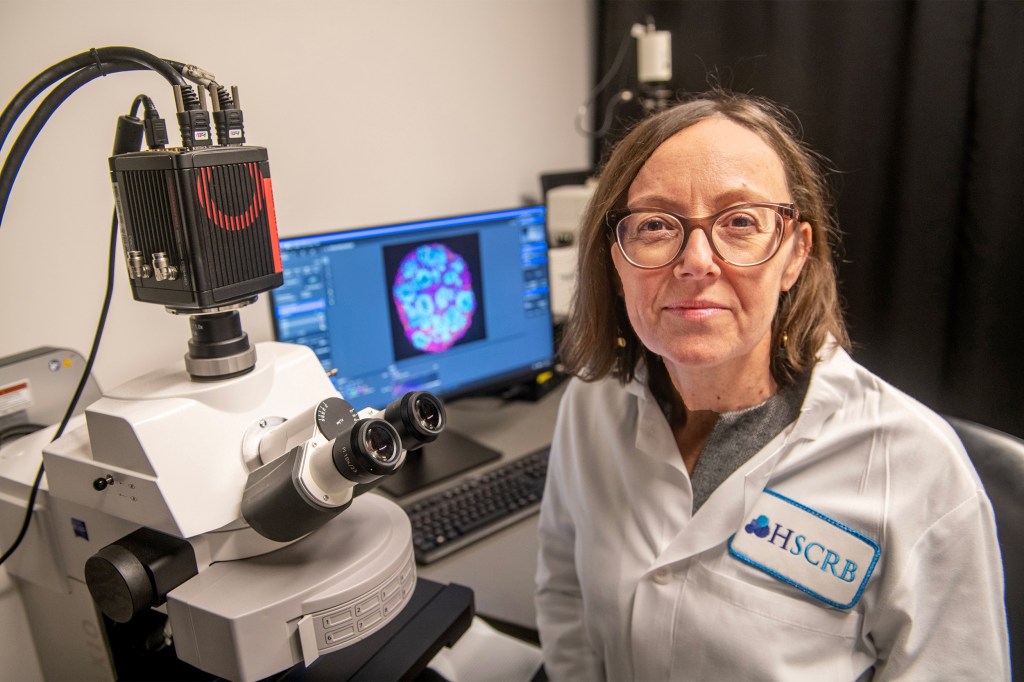

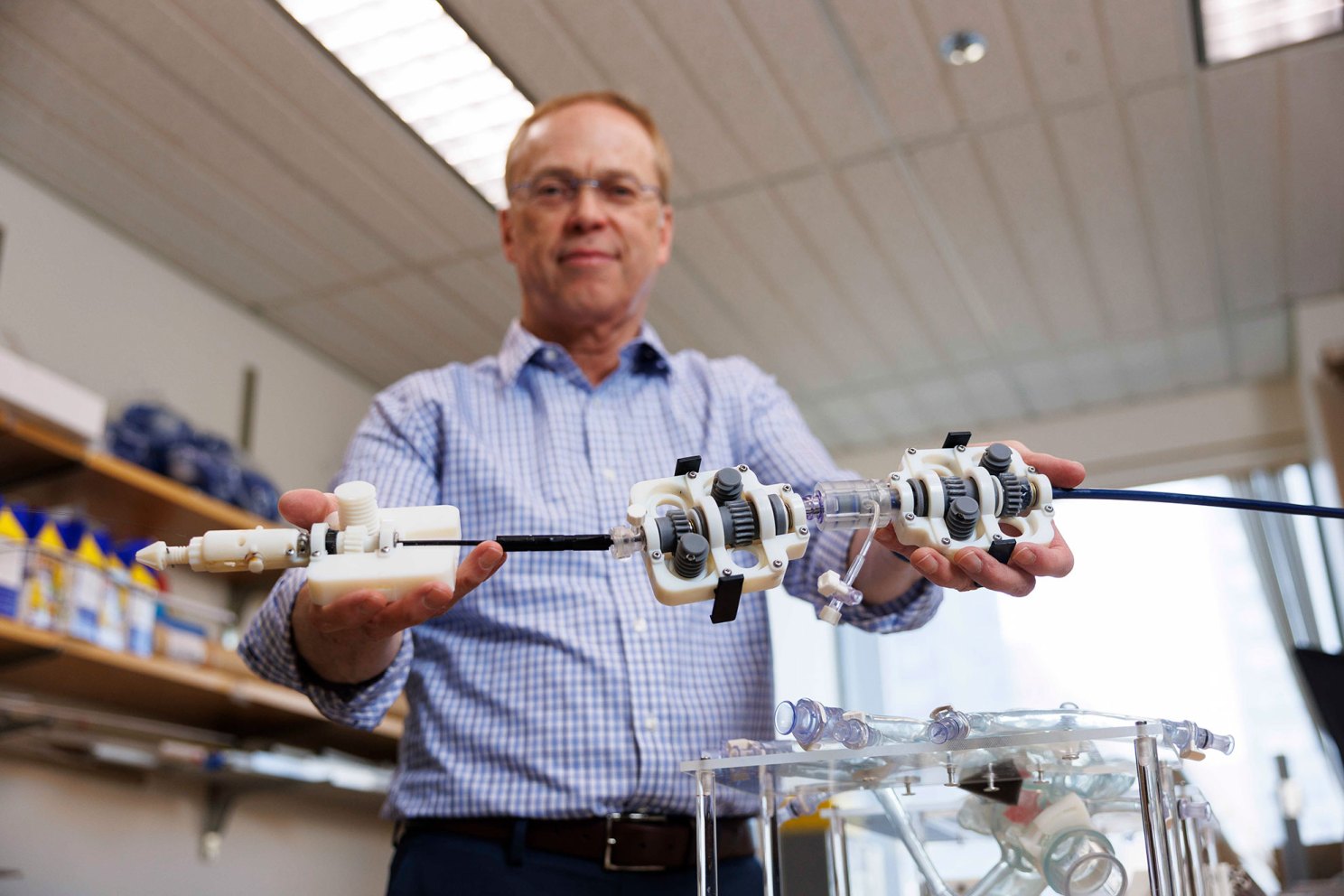

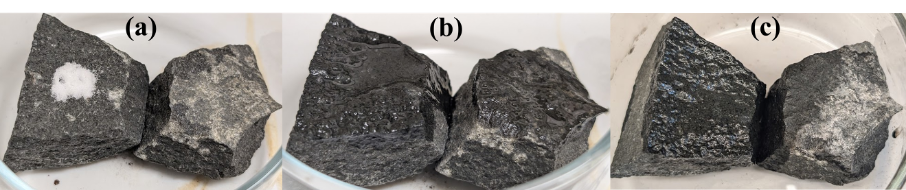

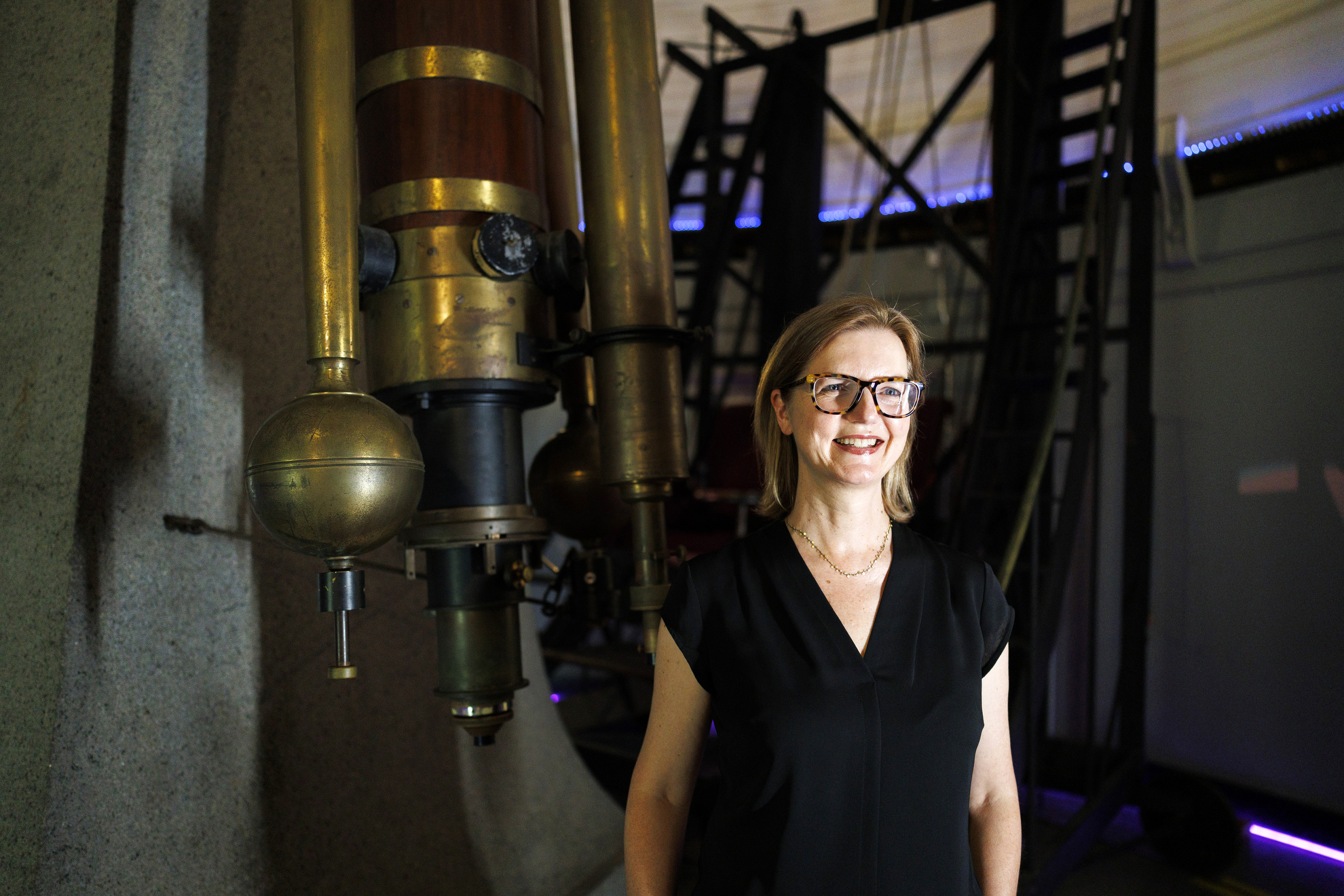

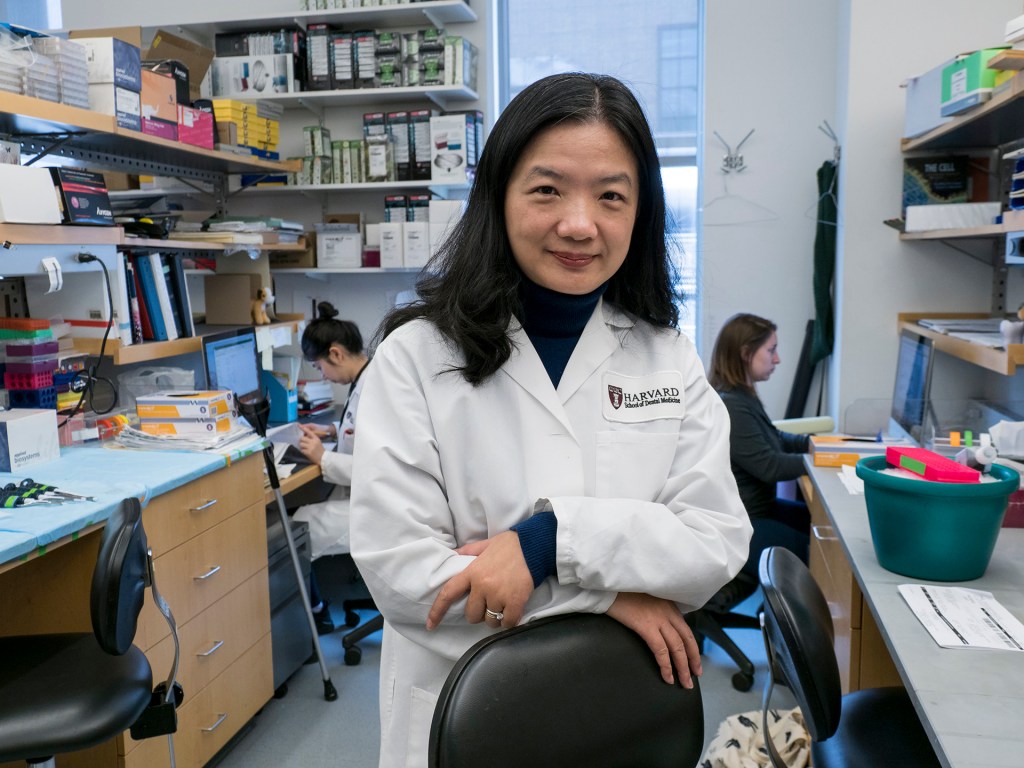

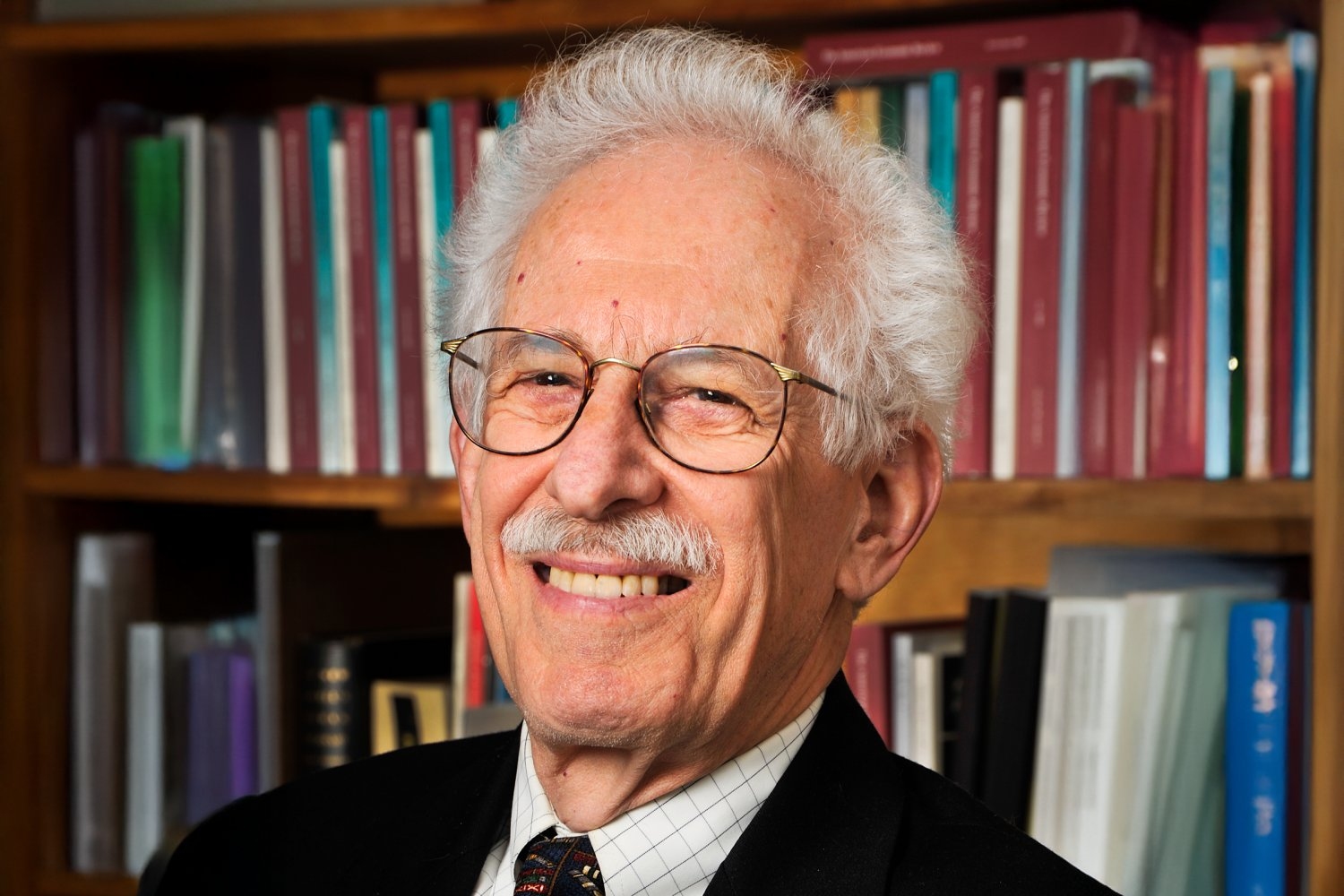

Katherine Koh.

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

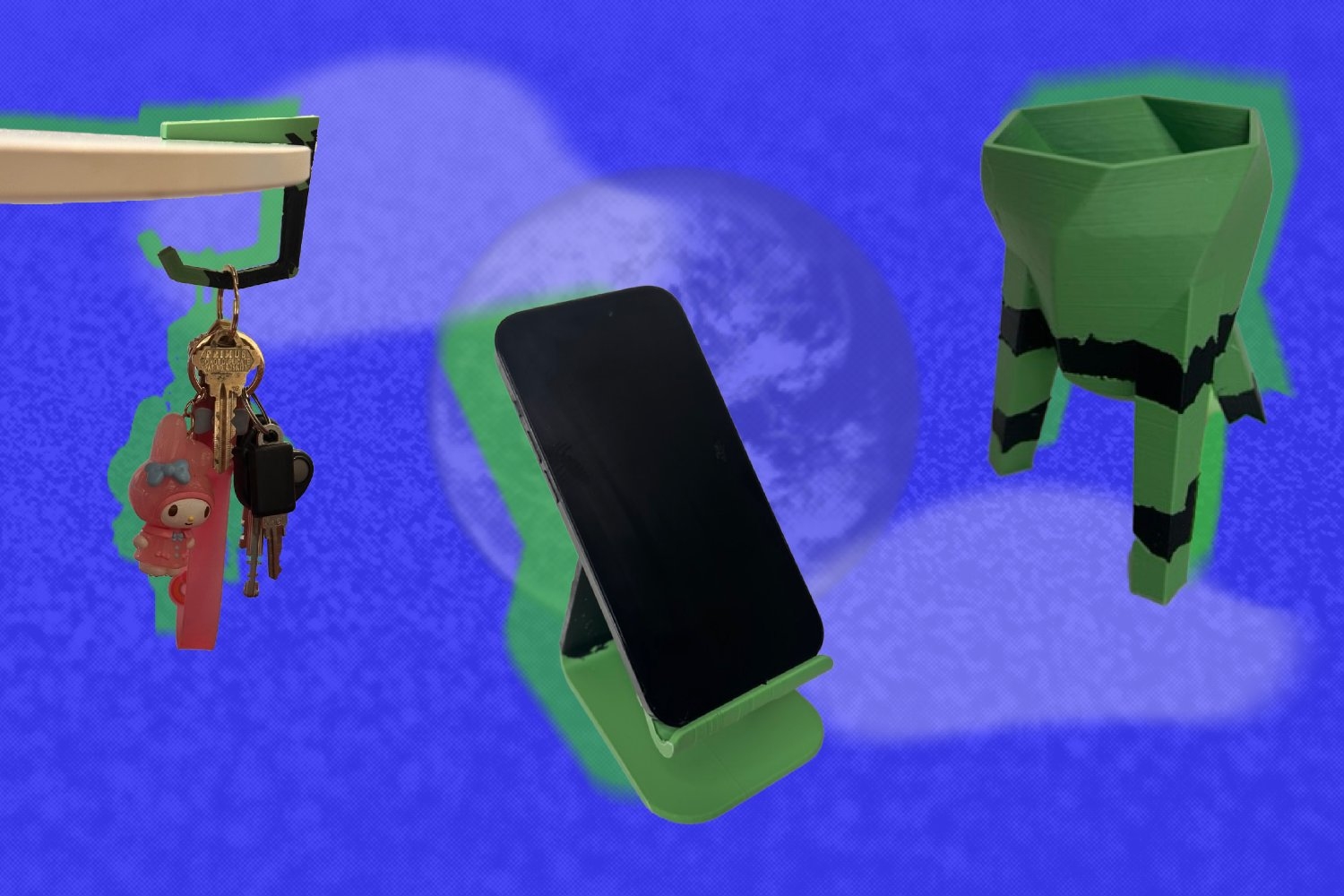

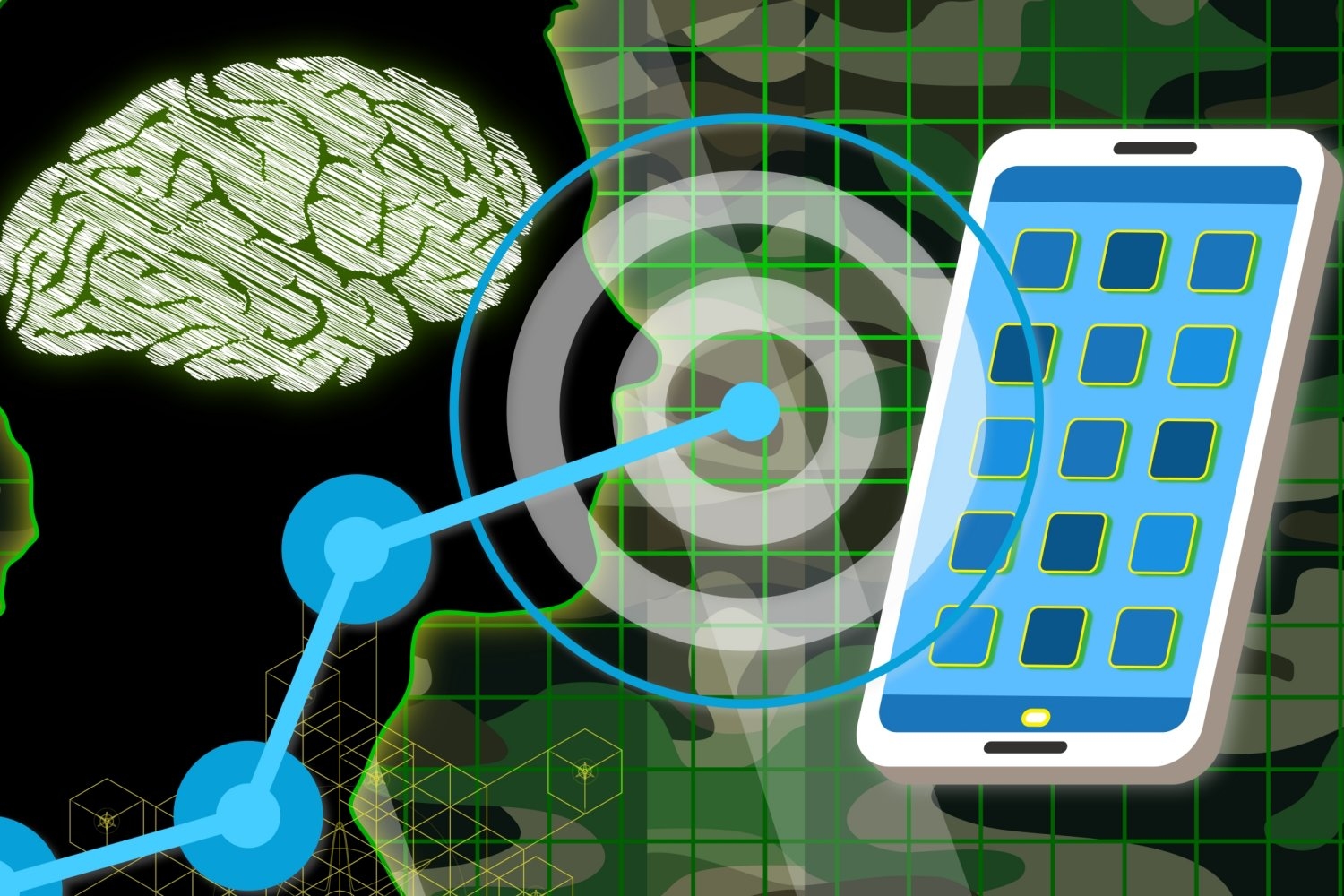

Cellphones are everywhere, including in the hands of homeless people, a population among America’s sickest — average life expectancy is just 51 — and among the hardest to reach by healthcare workers.

It’s also a population not often associated with technology, which comes with utility bills, internet service, and cellphone provider plans. But a pandemic era innovation — telehealth for homeless people — still offers a way for today’s providers to reach homeless patients more frequently and reliably than traditional office visits.

Katherine Koh, assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and a psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital and its partner Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, penned a recent article in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine highlighting the approach’s success at improving access and reducing barriers to care.

In this edited conversation with the Gazette, Koh said she’s seen the effect in her own practice, and she and co-authors from MGH, BHCHP, Boston Medical Center, and Brown University want to continue research on this approach and highlight its success for others assisting this hard-to-reach population.

How did your work in this area get started?

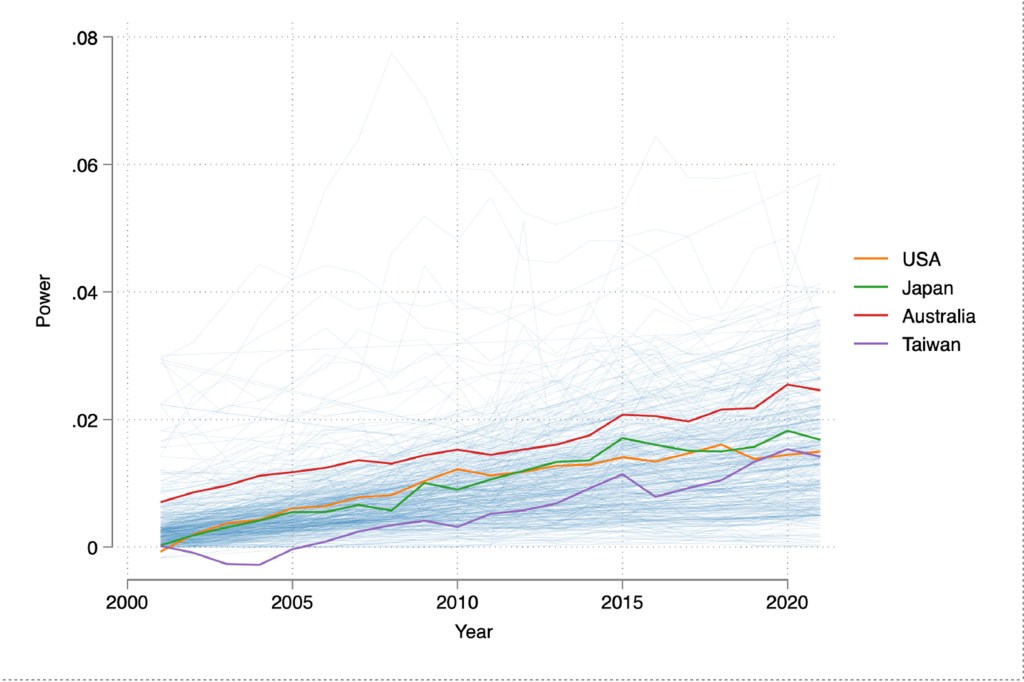

Like most healthcare organizations, BHCHP pivoted to telehealth during the pandemic in 2020. Initially, a lot of people — including myself — assumed it wouldn’t work well. But the patient-missed-appointment rate for my telehealth clinic days was lower than in-person days, which I found fascinating and counterintuitive.

“A lot of people are struggling with substance use, mental health symptoms, and executive functioning while trying to meet basic needs of food, water, and clothing, making it hard for people to come to a clinic appointment in a timely manner.”

Telehealth for unhoused patients may sound like an oxymoron, but upon reflection it actually makes sense. A lot of people are struggling with substance use, mental health symptoms, and executive functioning while trying to meet basic needs of food, water, and clothing, making it hard for people to come to a clinic appointment in a timely manner. They often need a T pass or a way to pay for the T. Telehealth creates an easier way for people to access care without having to contend with these barriers.

While there is a high missed-appointment rate when patients are expected to come in person, I found that with telehealth, about 80 percent of people would pick up their phones. For example, I talked to one patient every single week for about six months straight, whereas in person, he would come once a month at best. This article was born out of those clinical experiences.

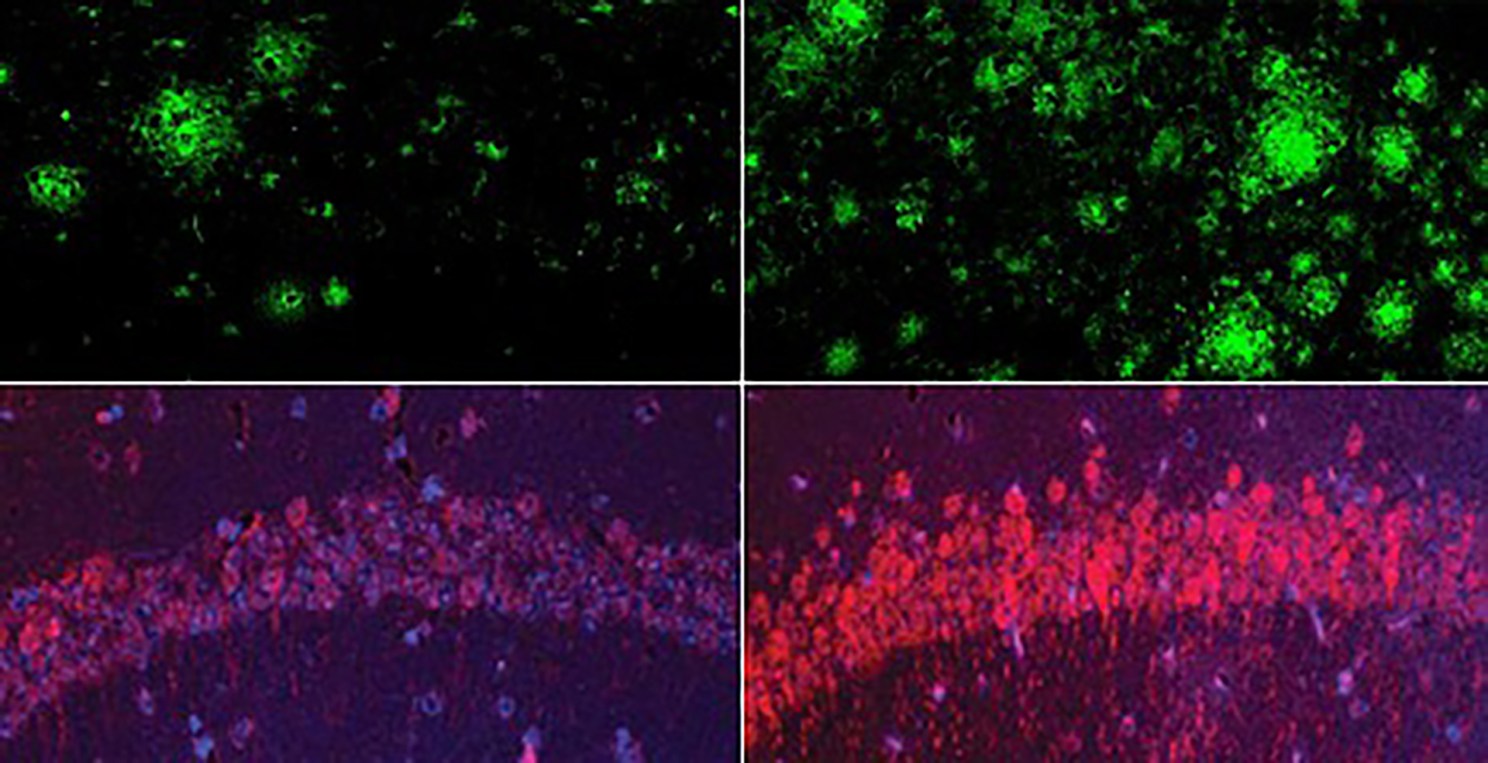

We did a preliminary analysis and found that during the first six months of the pandemic, 76 percent of behavioral health visits were done via telehealth, and 26 percent of medical visits. Arguably more fascinating is that telehealth is still being used now, when it doesn’t have to be. It’s still a common practice in BHCHP, and I think it should be optimized as a creative way to reach this population that’s often hard to reach.

Is it used more for particular conditions?

Behavioral health visits particularly lend themselves to telehealth, as a physical exam is not needed in many cases. We’ve also heard from our physician colleagues that it’s working especially well for diabetes follow-up visits, COVID-19 and other infectious diseases, and suboxone visits for opioid use disorder. It doesn’t work for every condition or patient, but we found that 50 percent of behavioral health patients have had one telehealth visit in the past year.

During telehealth visits, do you feel that you’re connecting with patients as much as you would in person?

Generally, yes, but I find there are nuances in how telehealth works for different patients. Most people can easily do an audio visit because it’s literally just picking up the phone. Video visits can be more challenging for patients because they require a stable internet connection and more tech literacy. However, another way we have made telehealth work is having a staff member set up an iPad to visit with a remote provider while patients are in our respite center or clinic, which has facilitated the use of video technology.

If it’s my first time meeting a new patient, audio visits are harder for establishing a connection than in person or via video. But if I know the patient, oftentimes an audio visit works very well to meet their needs. I often find patients expressing surprise and relief about the televisits, saying things like “This works for me.” I think it empowers them and encourages them to continue engaging in medical care.

“I think it empowers them and encourages them to continue engaging in medical care.”

What are the biggest healthcare issues facing homeless people today?

There are many. Few populations bear a greater psychiatric burden, which is what I’m focused on as a psychiatrist. When people think about homelessness and mental illness, they often think about those suffering schizophrenia, who are disconnected from reality. That is certainly prevalent, but much of what I treat is the sequelae of trauma. Many of these individuals have been through unimaginable trauma from an early age, which affects their ability to trust, to regulate emotions, to tolerate stressful situations. Substance use disorders are very prevalent: opioid use disorder and alcohol use disorder are the most common. Then there’s a whole range of acute and chronic medical diseases like cardiovascular disease, respiratory illness, and cancers. These conditions contribute to an abominable mortality rate and mean age of death that’s almost 30 years lower than the general population.

Are measures of health outcomes associated with this research?

Telehealth appears to increase engagement and access — typically two major challenges — for the unhoused population, but we don’t know yet whether this translates into fewer emergency and inpatient stays. That is a really important area of research.

This research also encourages the use of technology to address homelessness more broadly. For example, I’m working on a study using AI to measure outcomes for our patients, which I think is an exciting new area. Historically, homeless individuals have been excluded from advances in technology, but I think the telehealth example shows that technology can and should be used to creatively advance research and care for unhoused people.

“Historically, homeless individuals have been excluded from advances in technology, but I think the telehealth example shows that technology can and should be used to creatively advance research and care for unhoused people.”

Homelessness is at a record high in America. What factors are contributing to this?

Increasing housing costs, along with stagnant wages. An increase in migrants without adequate systems to address their influx, and the end of pandemic-era renter protections. Natural disasters are also an underappreciated reason for increasing homelessness. For example, in the 2024 count, people displaced as a result of the Maui wildfires were cited as contributing to the rise in homelessness.

A couple of years ago, the Mass and Cass homeless encampment — at Massachusetts Avenue and Melnea Cass Boulevard in Boston — was broken up, with homeless people sent to shelters, temporary housing, and some moving to other parts of the city. There has been media coverage that people have come back to that area. What’s your assessment of the situation there?

Tackling this crisis also has to be about prevention, because even if we were to house everybody who’s homeless today, we won’t solve the problem. There’s a whole pipeline of people falling into homelessness and not enough affordable housing and places to send them. My understanding is that the current Mass and Cass population is not just people returning, but also new people coming in. The centralization of services in that area — there are treatment programs, BHCHP, and shelters there — make it a natural place to congregate.

Addressing homelessness, which has many roots, in a large city, within budget constraints, is very complicated. Every major city is challenged by encampments and a lack of funding or support for sustainable solutions. At the patient level, I do think it’s critical to recognize that many unhoused people are there because of decades of trauma, adversity, and hardship. Their wounds can’t be healed within weeks or even months. Therefore, finding ways to fund temporary housing sites longer-term until people can move into permanent supportive housing, as well as increase the supply of affordable housing and focus on prevention for people at high risk, is key to solving this crisis.