Normal view

-

ETH News

-

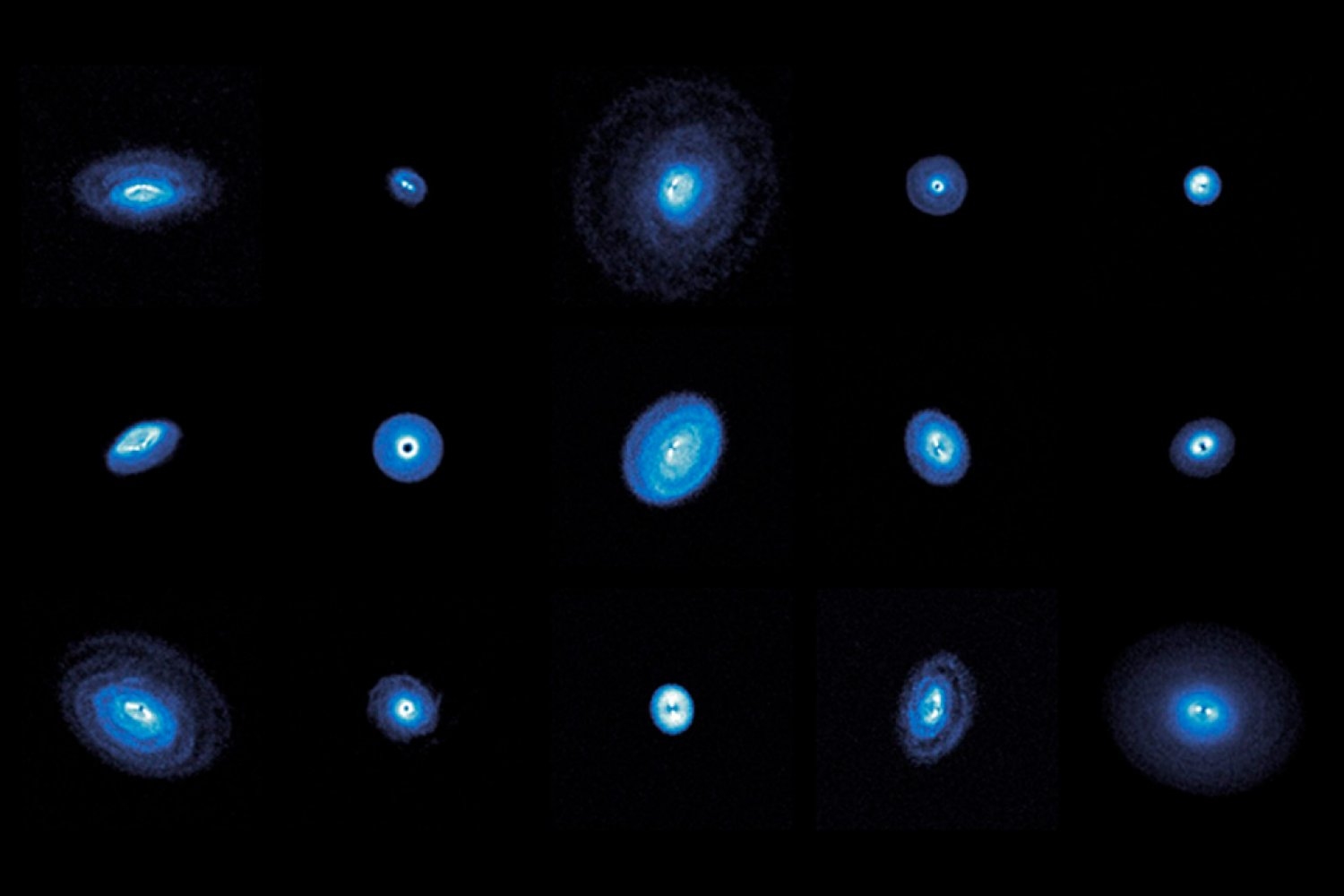

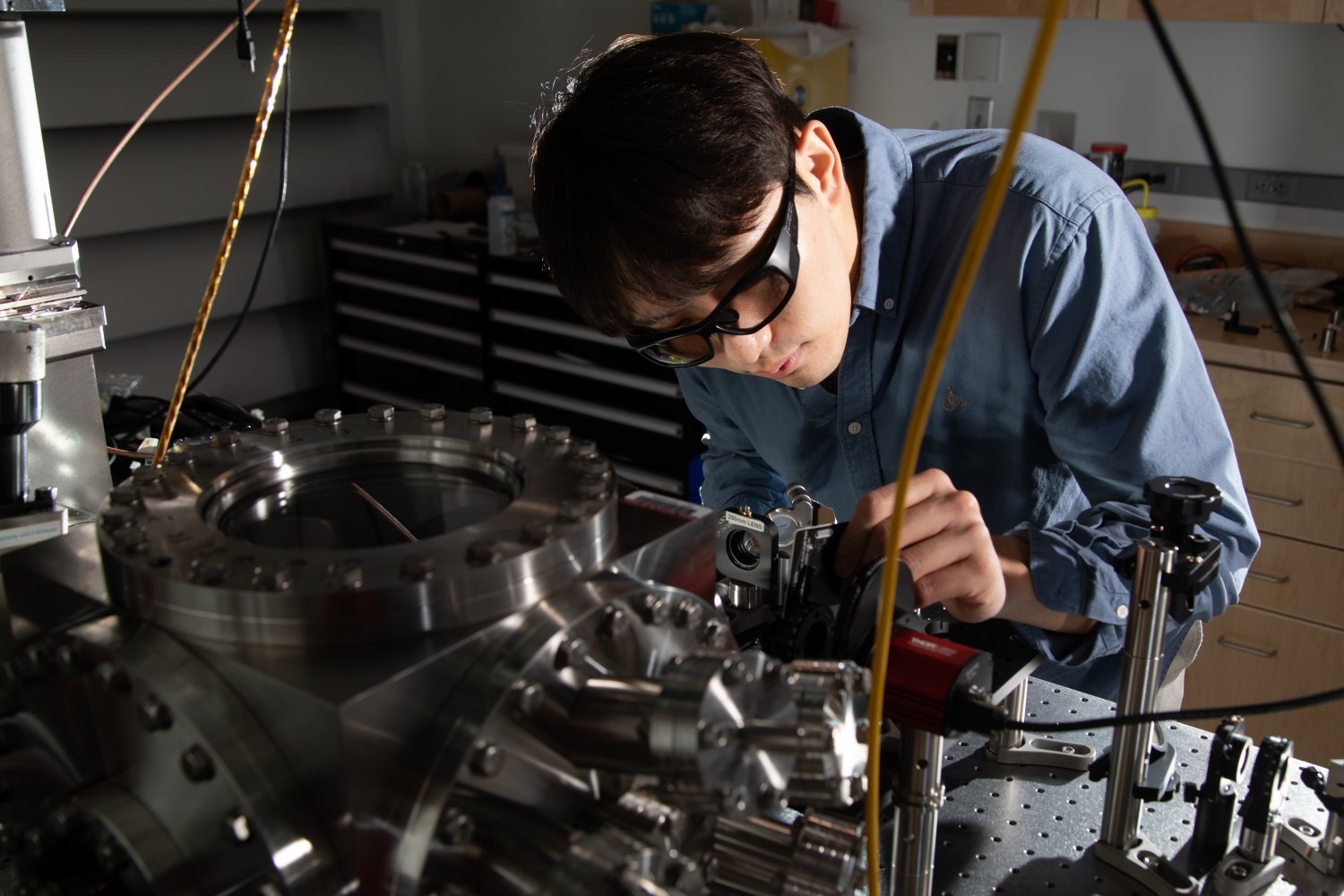

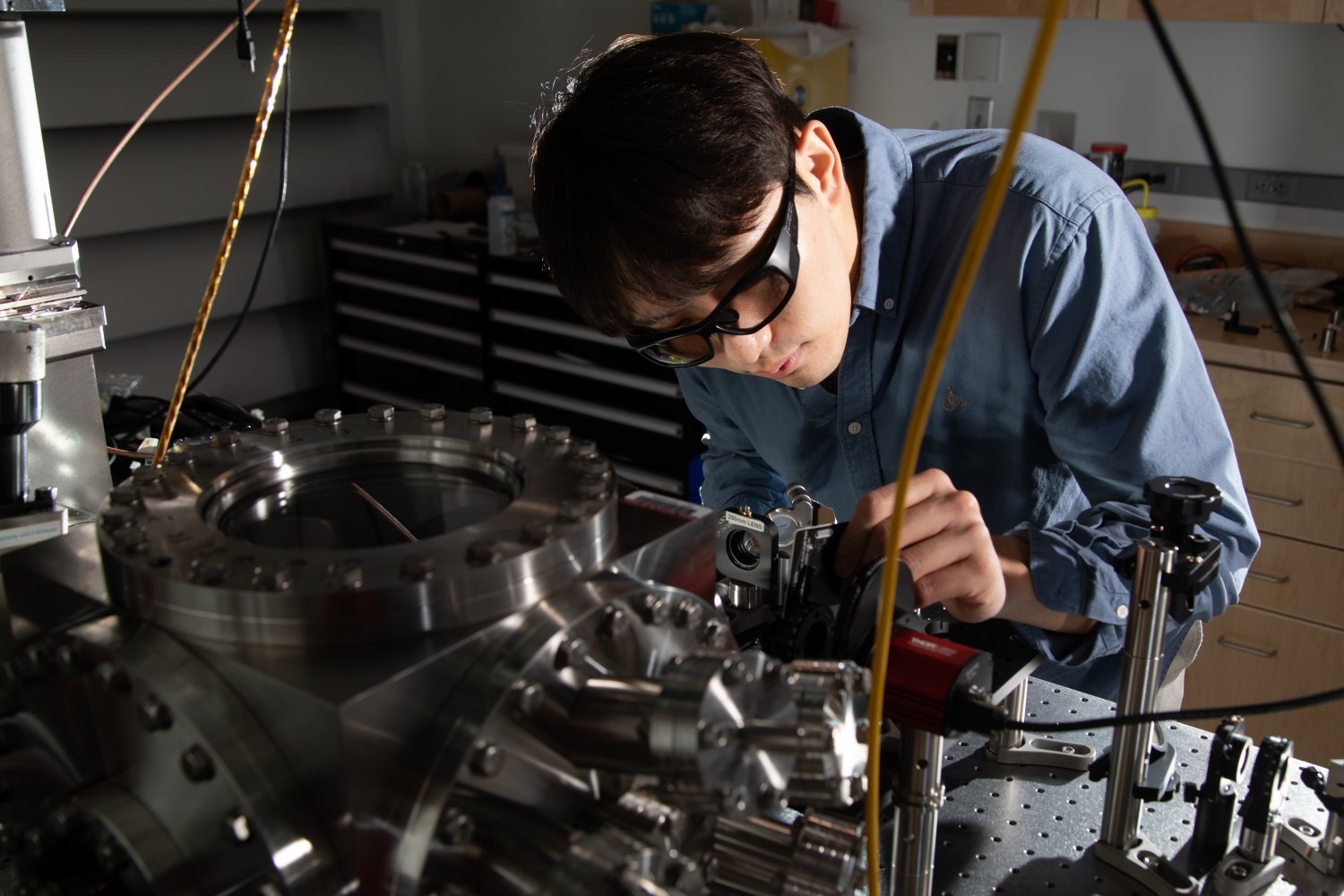

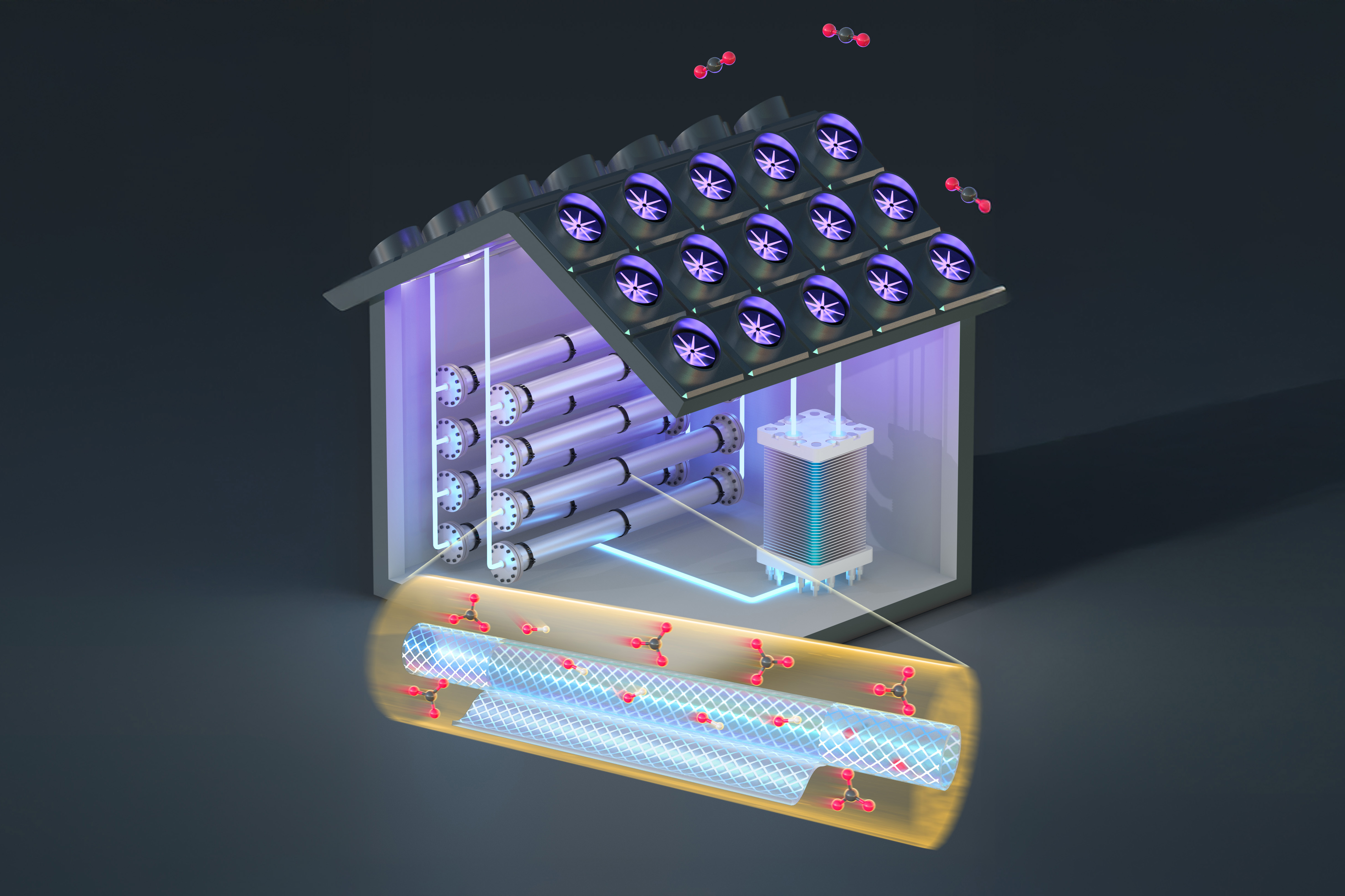

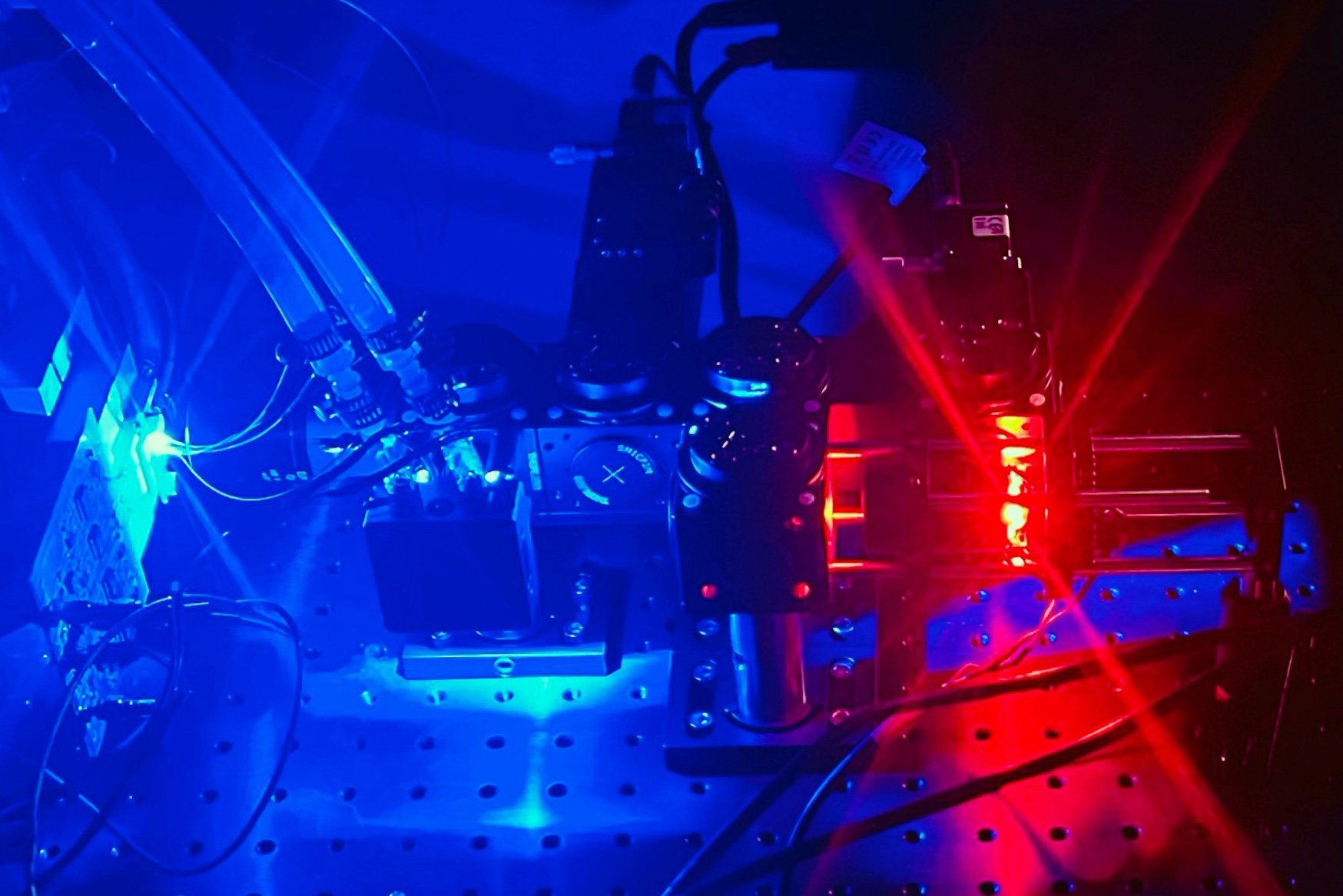

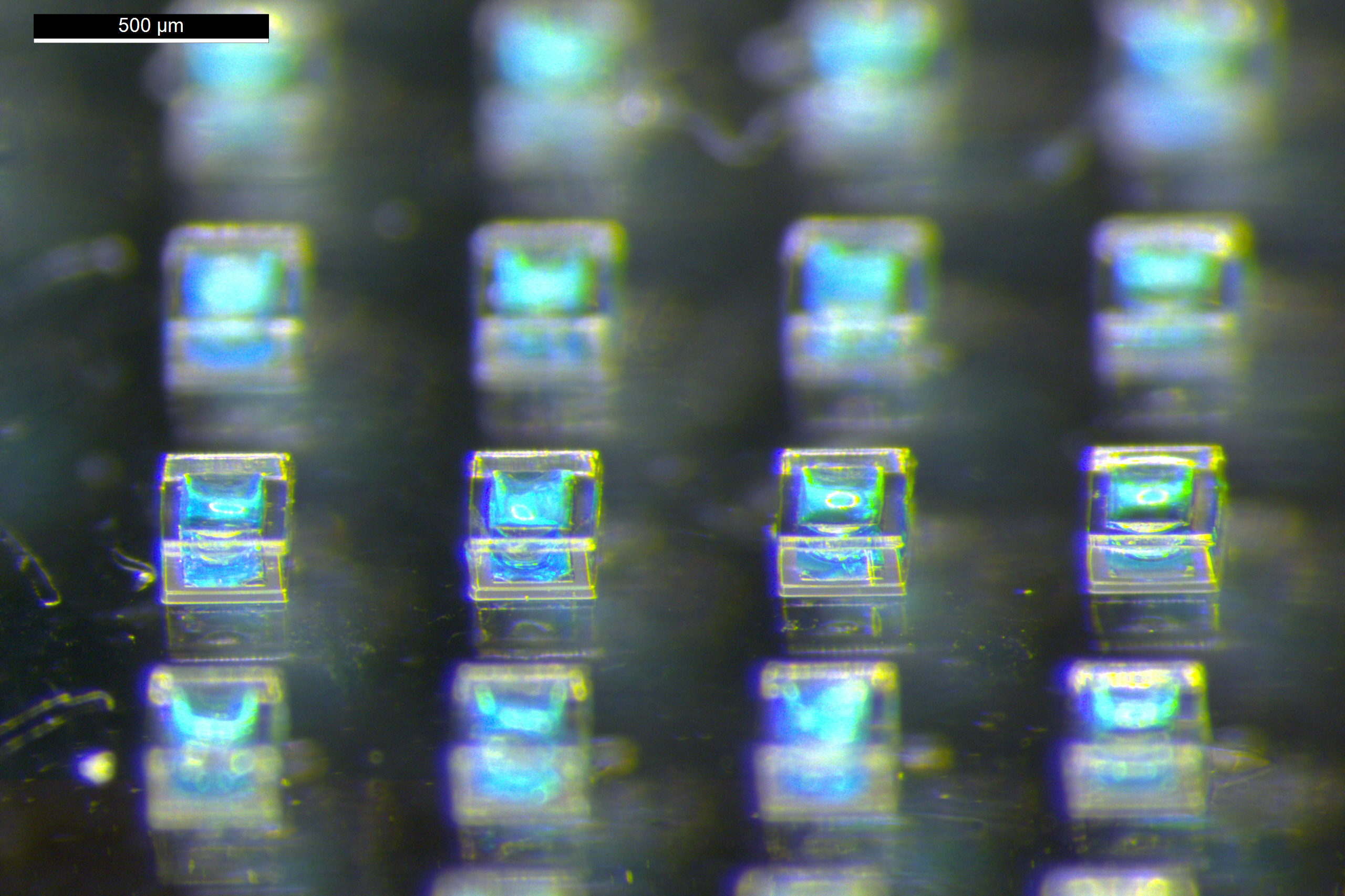

Ultra-thin lenses that make infrared light visible

Physicists at ETH Zurich have developed a lens with magic properties. Ultra-thin, it can transform infrared light into visible light by halving the wavelength of incident light.

-

MIT News

-

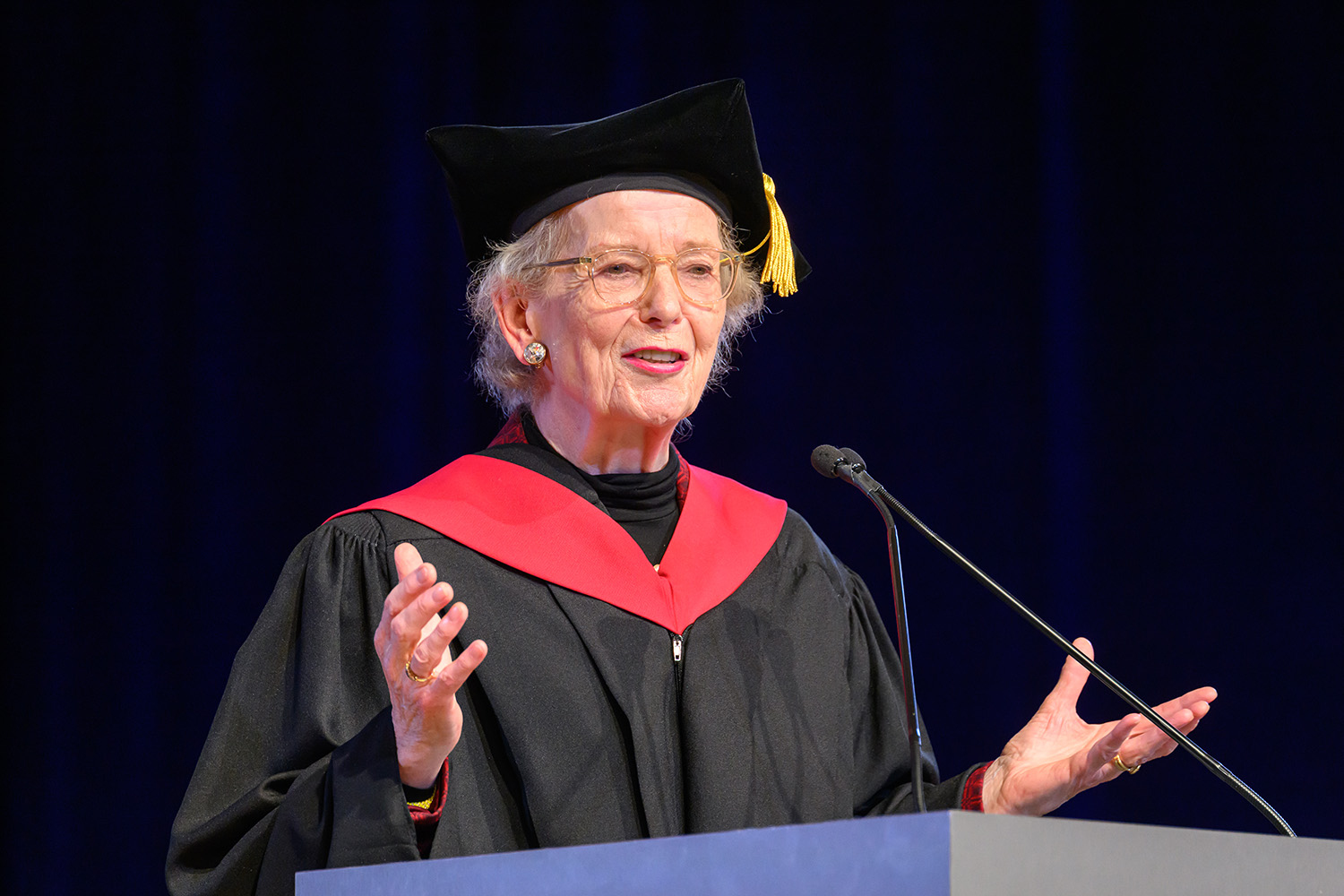

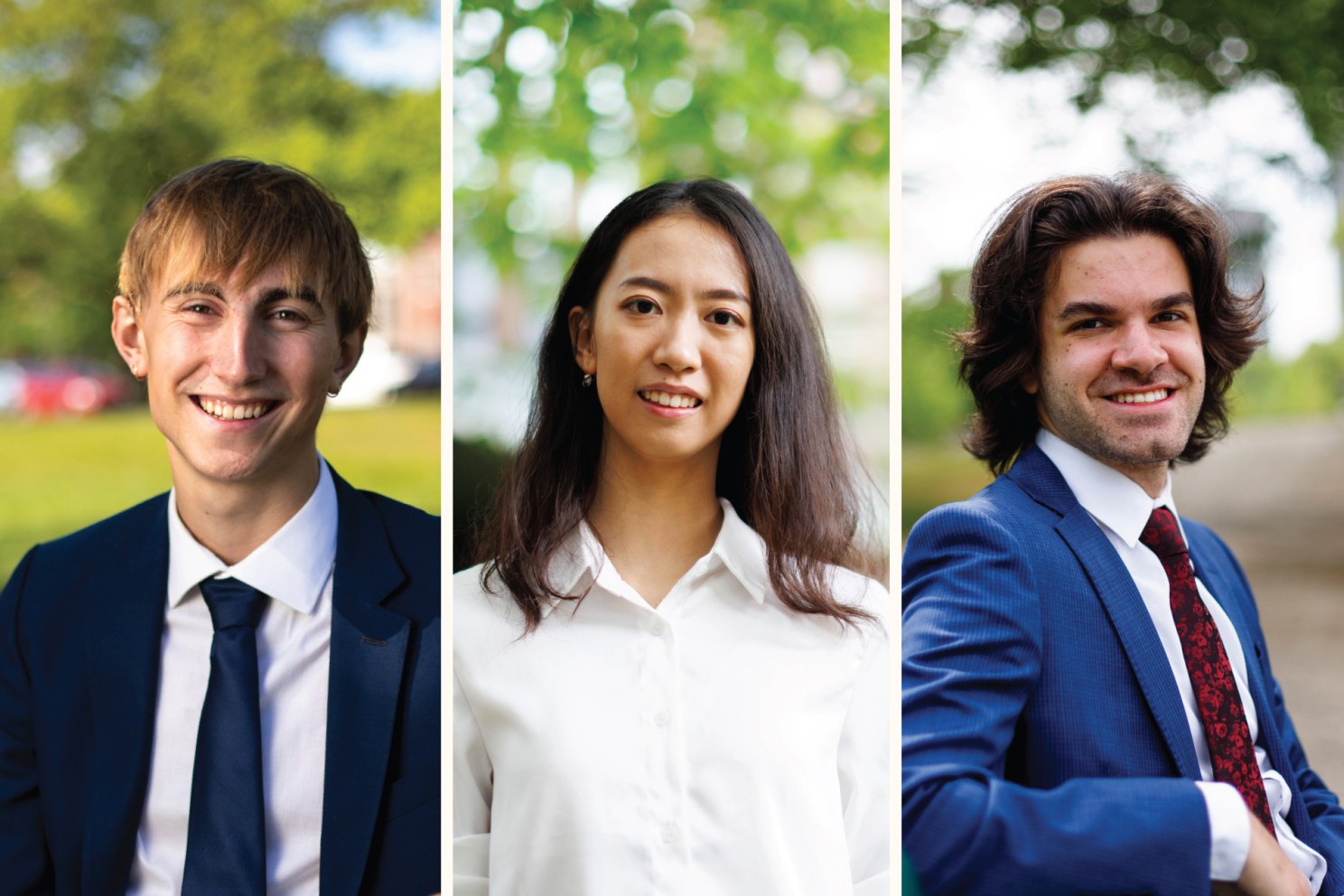

Mary Robinson urges MIT School of Architecture and Planning graduates to “find a way to lead”

“Class of 2025, are you ready?”This was the question Hashim Sarkis, dean of the MIT School of Architecture and Planning, posed to the graduating class at the school’s Advanced Degree Ceremony at Kresge Auditorium on May 29. The response was enthusiastic applause and cheers from the 224 graduates from the departments of Architecture and Urban Studies and Planning, the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, and the Center for Real Estate.Following his welcome to an audience filled with family and fri

Mary Robinson urges MIT School of Architecture and Planning graduates to “find a way to lead”

“Class of 2025, are you ready?”

This was the question Hashim Sarkis, dean of the MIT School of Architecture and Planning, posed to the graduating class at the school’s Advanced Degree Ceremony at Kresge Auditorium on May 29. The response was enthusiastic applause and cheers from the 224 graduates from the departments of Architecture and Urban Studies and Planning, the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, and the Center for Real Estate.

Following his welcome to an audience filled with family and friends of the graduates, Sarkis introduced the day’s guest speaker, whom he cited as the “perfect fit for this class.” Recognizing the “international rainbow of graduates,” Sarkis welcomed Mary Robinson, former president of Ireland and head of the Mary Robinson Foundation — Climate Justice to the podium. Robinson, a lawyer by training, has had a wide-ranging career that began with elected positions in Ireland followed by leadership roles in global causes for justice, human rights, and climate change.

Robinson laced her remarks with personal anecdotes from her career, from with earning a master’s in law at nearby Harvard University in 1968 — a year of political unrest in the United States — to founding The Elders in 2007 with world leaders: former South African President Nelson Mandela, anti-apartheid and human rights activist Desmond Tutu, and former U.S. President Jimmy Carter.

She described an “early lesson” in recounting her efforts to reform the laws of contraception in Ireland at the beginning of her career in the Irish legislature. Previously, women were not prescribed birth control unless they were married and had irregular menstrual cycles certified by their physicians. Robinson received thousands of letters of condemnation and threats that she would destroy the country of Ireland if she would allow contraception to be more broadly available. The legislation introduced was successful despite the “hate mail” she received, which was so abhorrent that her fiancé at the time, now her husband, burned it. That experience taught her to stand firm to her values.

“If you really believe in something, you must be prepared to pay a price,” she told the graduates.

In closing, Robinson urged the class to put their “skills and talent to work to address the climate crisis,” a problem she said she came late to in her career.

“You have had the privilege of being here at the School of Architecture and Planning at MIT,” said Robinson. “When you leave here, find ways to lead.”

© Photo: Justin Knight

-

Harvard Gazette

-

Harvard awards 9,434 degrees

Campus & Community Harvard awards 9,434 degrees Graduates celebrate as their School is announced in Tercentenary Theatre.Photo by Grace DuVal May 30, 2025 3 min read Totals reflect the 2024-25 academic year Part of the Commencement 2025 series A collection of features and profiles covering Harvard University’s 374th Commencement. On Thursday

Harvard awards 9,434 degrees

Harvard awards 9,434 degrees

Graduates celebrate as their School is announced in Tercentenary Theatre.

Photo by Grace DuVal

Totals reflect the 2024-25 academic year

Part of the Commencement 2025 series

A collection of features and profiles covering Harvard University’s 374th Commencement.

On Thursday the University awarded a total of 9,434 degrees. A breakdown of degrees and programs is listed below.

Harvard College granted a total of 2,014 degrees. Degrees from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences were awarded by Harvard College, the Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and the Graduate School of Design.

All Ph.D. degrees are conferred by the Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

All figures include degrees awarded in November 2024 and March and May 2025.

Harvard College

2,014 degrees

- 1,947 Bachelor of Arts

- 67 Bachelor of Science

Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

1,357 degrees

- 395 Master of Arts

- 275 Master of Science

- 7 Master of Engineering

- 680 Doctor of Philosophy

Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences

881 degrees

- 446 Bachelor of Arts (conferred by Harvard College)

- 67 Bachelor of Science (conferred by Harvard College)

- 7 Master of Engineering (conferred by GSAS)

- 26 Master in Design Engineering (conferred jointly with GSD)

- 79 Doctor of Philosophy (conferred by GSAS)

Harvard Business School

944 degrees

- 802 Master in Business Administration

- 78 Master in Business Administration with Distinction

- 49 Master in Business Administration with High Distinction

- 15 Doctor of Philosophy (conferred by GSAS)

Harvard Divinity School

140 degrees

- 50 Master of Divinity

- 79 Master of Theological Studies

- 10 Master of Religion and Public Life

- 1 Doctor of Theology

Harvard Law School

784 degrees

- 177 Master of Laws

- 602 Doctor of Law

- 5 Doctor of Juridical Science

Harvard Kennedy School

618 degrees

- 78 Master in Public Administration

- 249 Master in Public Administration (Mid-Career)

- 73 Master in Public Administration in International Development

- 206 Master in Public Policy

- 1 Ph.D. in Political Economy and Government (conferred by GSAS)

- 11 Ph.D. in Public Policy (conferred by GSAS)

Harvard Graduate School of Design

393 degrees

- 126 Master of Architecture

- 24 Master of Architecture in Urban Design

- 65 Master in Design Studies

- 55 Master in Landscape Architecture

- 3 Master of Landscape Architecture in Urban Design

- 45 Master in Urban Planning

- 14 Doctor of Design

- 26 Master in Design Engineering (conferred jointly with SEAS)

- 35 Master in Real Estate

Harvard Graduate School of Education

766 degrees

- 720 Master of Education

- 25 Doctor of Education Leadership

- 21 Doctor of Education/Philosophy

Harvard Medical School

484 degrees

- 82 Master in Medical Science

- 166 Doctor of Medical Sciences

- 236 Doctor of Dental Medicine

Harvard School of Dental Medicine

66 degrees

- 17 Master of Medical Sciences

- 12 Doctor of Medical Sciences

- 37 Doctor of Dental Medicine

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

561 degrees

- 374 Master of Public Health

- 155 Master of Science

- 18 Master in Health Care Management

- 14 Doctor of Public Health

Harvard Extension School

1,360 degrees

- 133 Bachelor of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies

- 1,227 Masters of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies

-

Harvard Gazette

-

No joke: He’s graduating

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer Campus & Community No joke: He’s graduating With family in mind — and big dreams for the future — Harvard employee Jorge Mendoza completes long journey to degree Nikki Rojas Harvard Staff Writer May 30, 2025 4 min read Part of the Commencement 2025 series A collection of features and profiles

No joke: He’s graduating

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

No joke: He’s graduating

With family in mind — and big dreams for the future — Harvard employee Jorge Mendoza completes long journey to degree

Nikki Rojas

Harvard Staff Writer

Part of the Commencement 2025 series

A collection of features and profiles covering Harvard University’s 374th Commencement.

Jorge Mendoza thought he was only joking when he told his then-girlfriend, now-wife, “Maybe one day I’ll go to school at Harvard.”

Years later, the joke, he’s happy to report, is on him.

“It actually came true!” says Mendoza, who graduated this week with a Bachelor’s in Liberal Arts in Extension Studies with a concentration on business administration and management.

Born in Colombia and raised in New York City, Mendoza joined Harvard as a custodial supervisor in 2018. Soon after, he enrolled at Harvard Extension School to pick up where prior college studies left off.

“To see the finish line, it’s unbelievable because it seemed so far,” said Mendoza, a 39-year-old father of two. “I’ve been in management for a very long time, so being able to do my business degree and knowing that this is what I want to do careerwise, it just made sense for me.”

“Jorge was one of those students who just came in and I saw determination to leave no stone unturned.”

Jill Slye

The six-year journey was far from easy. With help from Harvard’s Tuition Assistance Program, Mendoza immediately began to “chip away” at coursework, taking two courses per semester and a few over several summers. Two offerings on public speaking taught by Jill Slye were among his favorites.

Slye, in turn, praised Mendoza for his academic efforts.

“There are always students who tend to give off an energy that they are fully committed, right from the get-go,” she said. “They come into the class dedicated, open-minded, and nothing’s going to get in their way of learning. Jorge was one of those students who just came in and I saw determination to leave no stone unturned.”

Being a full-time employee and part-time student at Harvard offered Mendoza “insider knowledge” in his classes, he said. This spring Mendoza took an architecture class that incorporated a large number of buildings on campus, many of them familiar from his 9-to-5.

“Other people are joining the class from around the world,” he said. “They might be able to see pictures online and take some virtual tours. But to be able to be on campus, walk through or by the buildings, and even manage some of them gives you a unique [perspective],” he said.

Mendoza briefly considered skipping Commencement because it’s typically just another day on the job. “Then I really started getting excited about it.”

The only downside to being an employee who also takes classes is that you might not fully register the joy of being a Harvard student, Mendoza said. In fact, he briefly considered skipping Commencement because it’s typically just another day on the job.

But his mother and sisters told him that they wanted to be a part of the tradition, and his wife challenged his lack of enthusiasm. “Then I really started getting excited about it, and I said, ‘You know what? This is different. This is my Commencement. This is what I’ve worked so hard for,’” he said.

He’s also worked hard to serve as a role model to his kids.

“I want them to be able to say, ‘My dad finished while we were here,’” he said. “’He did it with kids and a family.”’

And that’s one big reason he’s not done yet. Mendoza has his eyes on a new goal: a master’s in liberal arts in sustainability from the Extension School.

“I hope to continue to grow academically, because I love to learn,” he said. “I want to go back to focus on sustainability. It’s a focus of the University and of the world. It is something I want to focus on to grow and develop in my career and to continue to make an impact.”

-

Princeton University

-

Liat Krawczyk named inaugural executive director of the NJ AI Hub

Princeton is one of four founding partners of the Hub, along with the New Jersey Economic Development Authority, Microsoft and CoreWeave.

Liat Krawczyk named inaugural executive director of the NJ AI Hub

Pensions Minister sees pioneering biotech research at Imperial

-

Princeton University

-

Princeton Research Day 2025: A pipeline of talent and commitment

The University event for early-career researchers and creators to present their work celebrated its 10th anniversary.

Princeton Research Day 2025: A pipeline of talent and commitment

-

California Institute of Technology (Caltech)

- Kyle Chen and Indeever Madireddy Receive Goldwater Scholarship Awards

-

ETH News

-

What ETH glacier researchers know about the collapse of the Birch Glacier

On Wednesday, the glacier known as Birchgletscher collapsed under the weight of rock and debris from rock avalanches on Kleines Nesthorn. In a factsheet, ETH researchers explain the background to the catastrophic collapse that buried the village of Blatten.

What ETH glacier researchers know about the collapse of the Birch Glacier

-

NUS - National University of Singapore Newsroom

-

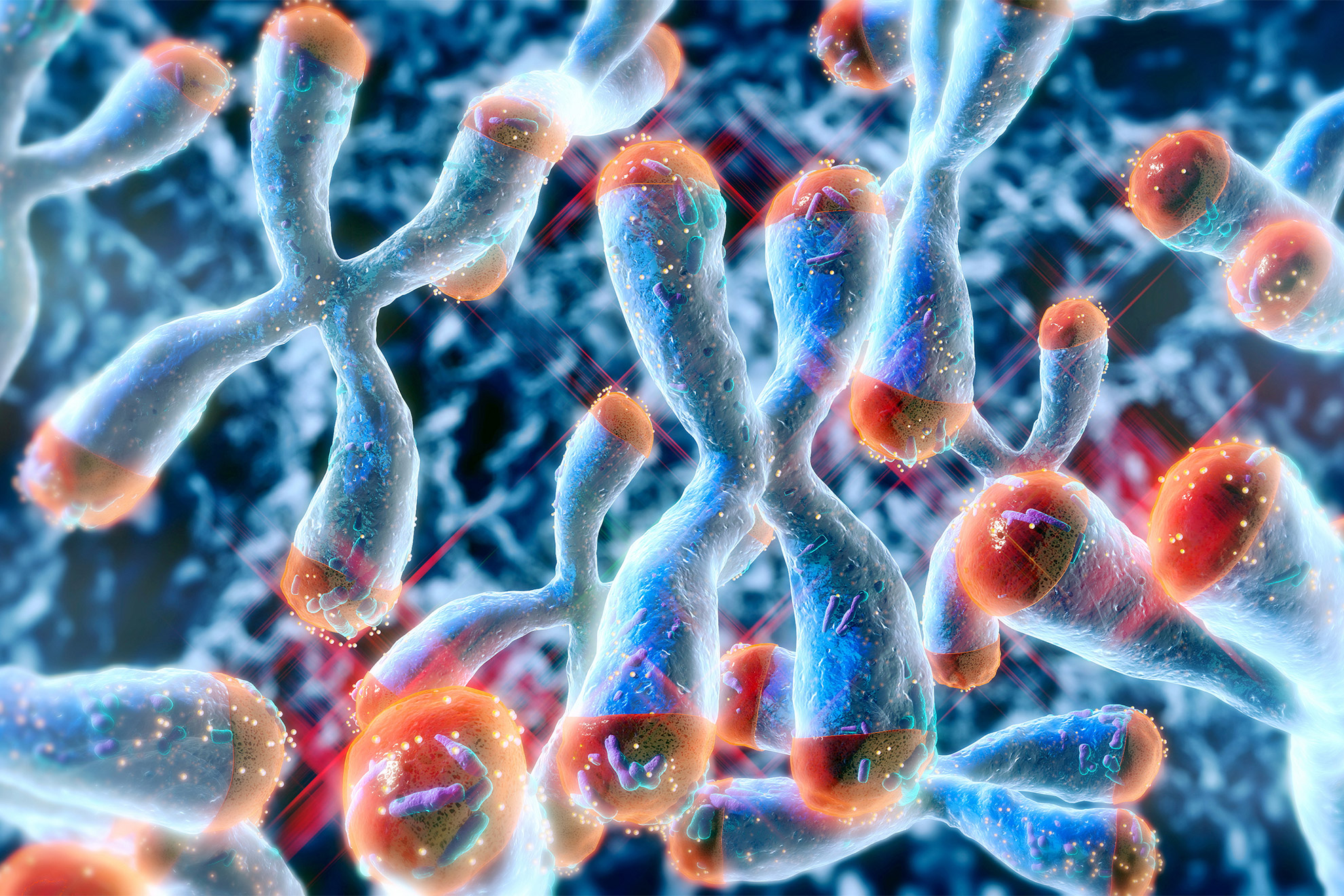

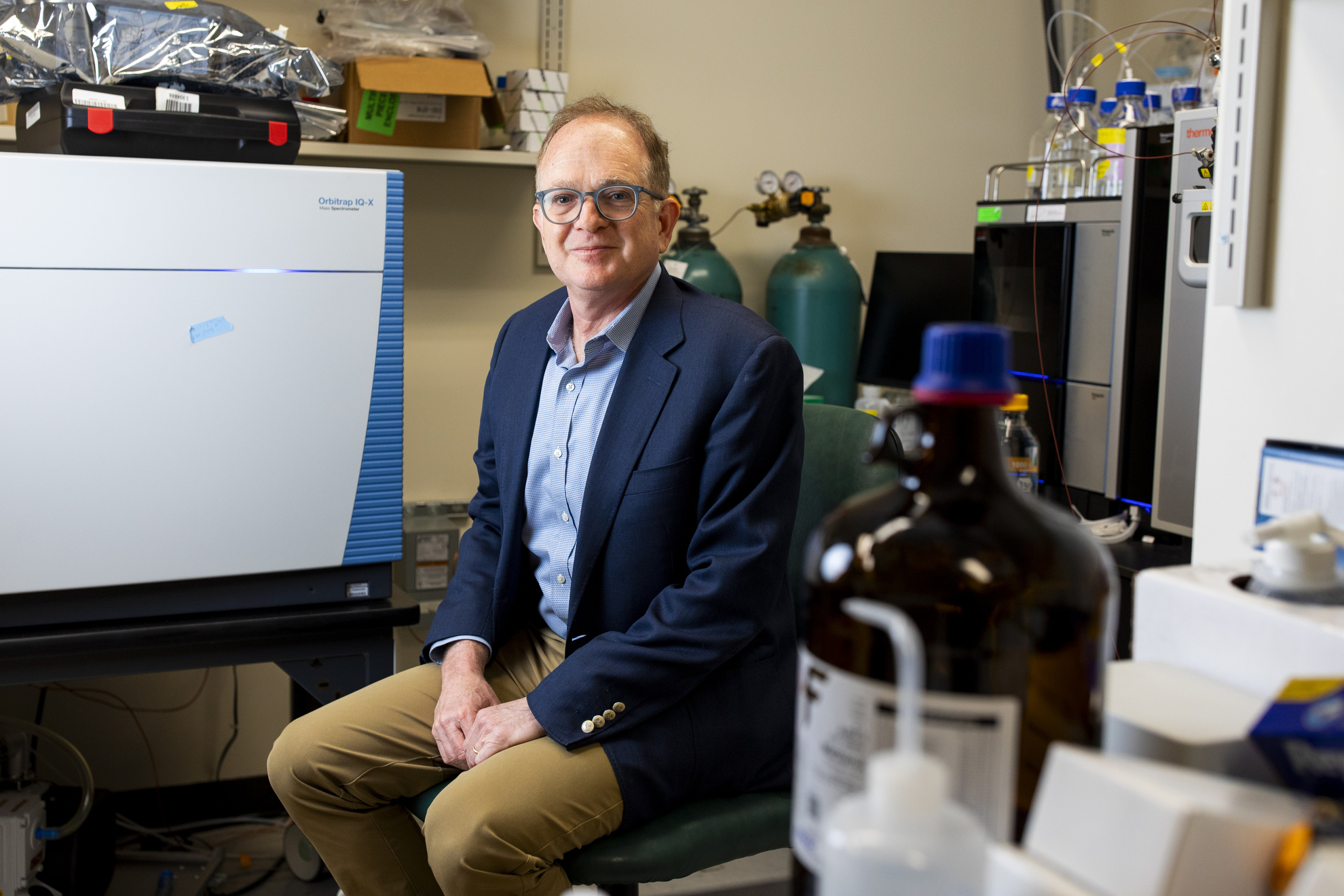

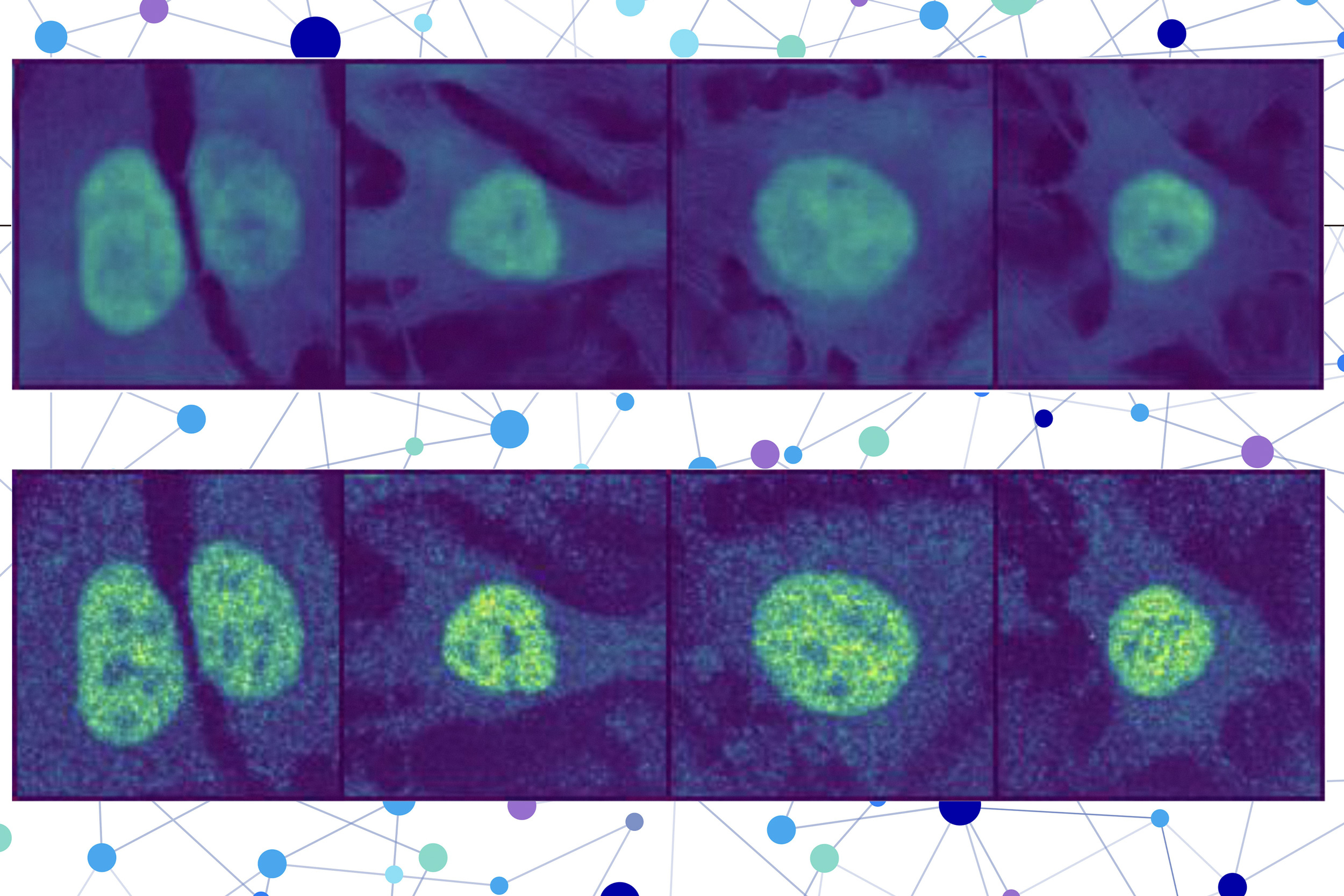

Framework for analysing large-scale metabolomic data

Statisticians from the National University of Singapore (NUS) have developed a pioneering approach for analysing population-scale metabolomic data, marking a major advancement in the precision and depth of metabolic profiling. This new method promises to improve both personalised healthcare and preventive medicine by improving the accuracy and interpretability of metabolic analyses.The pioneering framework, developed by a team of researchers led by Associate Professor Yao Zhigang from the Depart

Framework for analysing large-scale metabolomic data

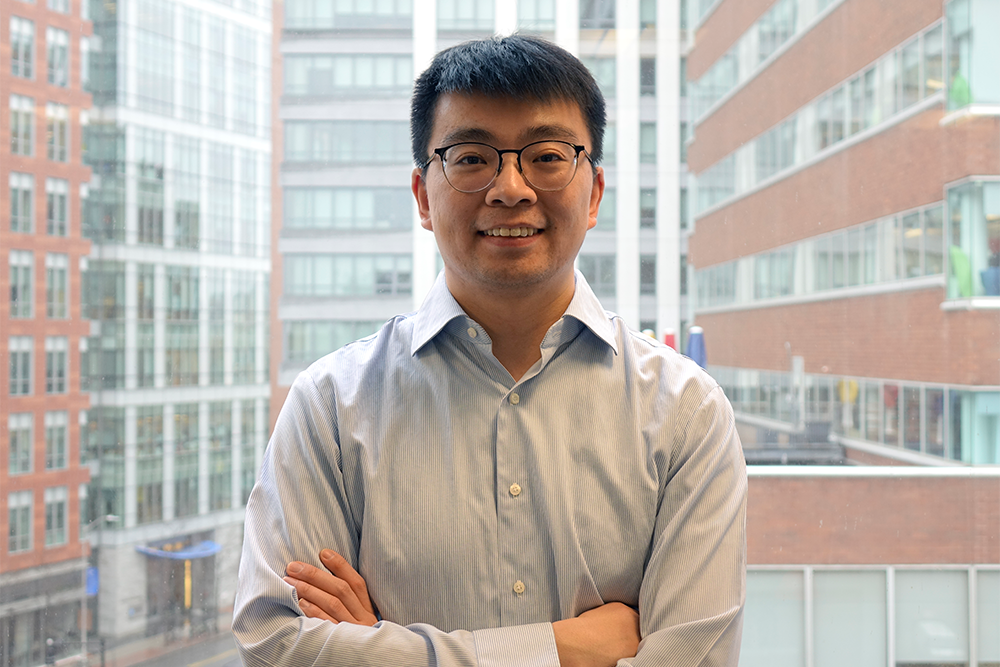

Statisticians from the National University of Singapore (NUS) have developed a pioneering approach for analysing population-scale metabolomic data, marking a major advancement in the precision and depth of metabolic profiling. This new method promises to improve both personalised healthcare and preventive medicine by improving the accuracy and interpretability of metabolic analyses.

The pioneering framework, developed by a team of researchers led by Associate Professor Yao Zhigang from the Department of Statistics and Data Science at the NUS Faculty of Science, employs advanced mathematical techniques to fit low-dimensional manifolds into the high-dimensional space of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)-based metabolic biomarkers. This effectively reduces noise and reveals meaningful patterns associated with metabolic change. It can be used to better stratify individuals based on their metabolic profile and associated risk of disease. The research was carried out in collaboration with Professor Yau Shing-Tung of Tsinghua University.

Their findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America on 28 May 2025.

Exploiting manifold fitting techniques to decipher metabolic heterogeneity

Metabolomic profiling, particularly through NMR-based biomarkers, offers rich insights into human metabolism. However, the complexity and dimensionality of such data have long challenged conventional analytical techniques. Traditional methods often struggle to uncover the subtle and structured biological variations underpinning disease risks.

The new framework represents a significant advancement in overcoming these limitations. It begins by clustering 251 metabolic biomarkers—measured from over 210,000 participants in the UK Biobank—into seven biologically meaningful categories, reflecting the modular organisation of human metabolism. Manifold fitting is then applied to each category to reveal smooth, low-dimensional structures that capture the essential variations in metabolic states.

At the core of this framework is the manifold fitting module, which models how individuals are distributed in a low-dimensional space based on their metabolic profiles. This geometric representation not only reduces noise but also enhances interpretability by uncovering coherent metabolic patterns that correlate with health and disease outcomes.

The key innovation lies in the method’s ability to stratify the population. In three of the seven categories, the fitted manifolds clearly divide individuals into two major subgroups, each associated with distinct risks for conditions such as metabolic disorders, cardiovascular disease, and autoimmune conditions.

During a plenary lecture at the 2025 International Congress of Chinese Mathematicians (ICCM), Assoc Prof Yao explained, "The new approach allows us to identify meaningful metabolic subgroups by fitting low-dimensional manifolds to high-dimensional biomarker data. This will significantly improve our ability to relate metabolic states to susceptibility to disease."

Compared to traditional analyses, this manifold-based framework demonstrates superior performance in preserving biological signals, identifying disease-relevant subgroups, and aligning with demographic, clinical, and lifestyle factors. These strengths position it as a powerful tool for metabolic research and precision health applications.

Future directions: Advancing genetic and longitudinal insight into metabolic health

Building on the success of this framework, the research team is now exploring several promising directions to deepen their understanding of metabolic heterogeneity and its clinical implications.

One key avenue involves integrating genetic data with the identified metabolic subgroups. By conducting genome-wide association studies within each manifold-defined subgroup, the researchers aim to uncover genetic variants linked to specific metabolic patterns. This could provide critical insights into the hereditary basis of metabolic diversity and help elucidate the genetic architecture underlying complex metabolic traits and their associated disease risks.

Another focus is the longitudinal analysis of metabolic manifolds to assess their stability over time and evaluate their potential as predictive biomarkers. By analysing time-series metabolomic data, the team seeks to trace how individuals transition between metabolic states over time and determine whether these shifts are associated with disease onset or progression. Such findings could pave the way for early detection systems and more precisely timed preventive interventions.

“Our framework not only captures the current structure of metabolic variation but also lays the foundation for investigating its genetic origins and temporal dynamics. These future directions could significantly enhance personalised healthcare by enabling earlier and more targeted responses to metabolic risk,” added Assoc Prof Yao.

This ongoing research continues to expand the frontiers of metabolic profiling, providing a robust and adaptable platform for population health studies and precision medicine.

Imperial’s annual celebration of science and arts nearly here

-

NUS - National University of Singapore Newsroom

-

At NUS College, Wednesdays are for community

Under the NUSOne initiative, the freedom to spend Wednesday afternoons pursuing out-of-classroom activities has given NUS students more opportunities to develop a richer, more holistic student life. Students have spent the time learning about sustainability and serving the community, equipping them with skills ranging from entrepreneurship to cookery and crafts, while building bridges with other segments of society.At NUS College (NUSC), this allocated time has been turned into a community-build

At NUS College, Wednesdays are for community

Under the NUSOne initiative, the freedom to spend Wednesday afternoons pursuing out-of-classroom activities has given NUS students more opportunities to develop a richer, more holistic student life. Students have spent the time learning about sustainability and serving the community, equipping them with skills ranging from entrepreneurship to cookery and crafts, while building bridges with other segments of society.

At NUS College (NUSC), this allocated time has been turned into a community-building opportunity for faculty, staff, and students, some of whom live off-campus, with the rest spread across two residential colleges.

Inspired by weekly family meals that help families remain close even as children grow up and start to lead independent lives, Associate Professor Eleanor Wong, NUSC Vice Dean (Residential Programmes & Enrichment), proposed making Wednesday afternoons and evenings the default timing for all NUSC events.

“We want to create a regular time when members of the NUSC community – students, staff and faculty, past and present – know that if they ‘come home’ to NUSC during this time, there will always be some other members of our family there, there will always be some activity going on, and there will always be the chance to catch up with each other,” said Prof El, as she is fondly known on campus.

Thus was born “Wednesdays at NUSC”, an initiative that consolidates both student- and staff-led events into a consistent schedule of opportunities for the community to gather. The first run took place in Semester 2 of AY2024/2025 and the initiative is set to continue in the new academic year.

The NUS College Club, a constituent club of the NUS Students’ Union that represents the NUSC student community, leads the planning together with NUSC staff advisors by creating a list of event themes at the start of the semester and sending out a call for proposals. The college’s Student Life Team further supports them by facilitating collaboration among the committees and assisting with logistics and funding to make the ideas happen.

Every Wednesday of the past semester (except for Reading Week and Exam Week), the students have gathered for activities like watching movies, engaging in arts and crafts, and enjoying performances by NUSC interest groups. Casual gatherings were interspersed with structured events such as town hall meetings, start- and end-of-semester dinners, and a Valentine’s Day carnival with nostalgic activities and treats such as a bouncy castle and old-school ice cream.

The results have been “very encouraging,” said Prof El, who observed that the events attract consistent attendance from students and even some alumni. There is no pressure to attend every event, but with a wide variety to choose from, the hope is that most members of the NUSC community will attend at least a few in each semester and Wednesdays at NUSC will become a tradition that draws them back “home” whenever they can spare the time.

Combined efforts yield bigger, better events

Students have reacted positively to the initiative, with some noting that the fixed schedule aligned with their common free time makes it more convenient to attend the events. Those involved in organising the events also appreciate the additional support to make their efforts more impactful, since the initiative provides some funding and encourages collaboration between student interest groups.

“Previously, there were a lot of smaller-scale events planned by specific groups and the reach of each one was smaller. But when two committees collaborate, we can publicise the event via two channels and have greater reach,” shared Larissa Yong, a second-year Data Science and Analytics student with a second major in Quantitative Finance who served as vice president of community life in the NUS College Club for AY2024/2025.

“A lot of us also try to make it every Wednesday, since we know beforehand that there will be something to attend.”

The NUS College Club is now brainstorming ideas for the next semester, with possible activities including a primary school-style sports day featuring three-legged races and hula hoop games, as well as an arts-themed night to showcase student performances.

Ymir Meddeb, a third-year Computer Engineering major and director of NUSC’s Student Affairs Committee, said the Wednesdays at NUSC initiative helped his committee make this year’s combined NUSC Cultural Night and Chinese New Year Celebrations the largest edition of their diversity-themed events so far. Students and alumni set up about 10 booths with activities and food showcasing different cultures, traditions and religions, and the event attracted a turnout of about 120 students.

“It was stressful and took quite a bit of coordination with other committees, but when people started flooding in at the event, I felt like ‘Wow, I did that!’” he said.

With more opportunities to interact across cohorts, bond over shared interests, and try out new experiences like performing in front of an audience, first-year students like Psychology major Syed Ariq Miiad can integrate more quickly into the college, fostering a stronger sense of community and well-being among the students.

Miiad participated in several events where the Livecore (music and band) interest group was involved, quickly made friends with students who shared his interest, and ended up joining the group’s organising committee within his first year.

Said Summer Fong, a Year 2 Mechanical Engineering major: “Having these regular events makes the dorm experience much livelier, which is really important to help people feel like NUSC is their home, rather than their bedroom.”

Having an event to look forward to every Wednesday is also good for mental health, Miiad noted. “It offers something to do in the mid-week when you need to relax and take a break from academic work, and this is a way that people can use the time to chill and engage in community bonding.”

He added: “I feel that these events are important for well-being. Most people will probably choose to attend them rather than being alone in their rooms.”

-

Harvard Gazette

-

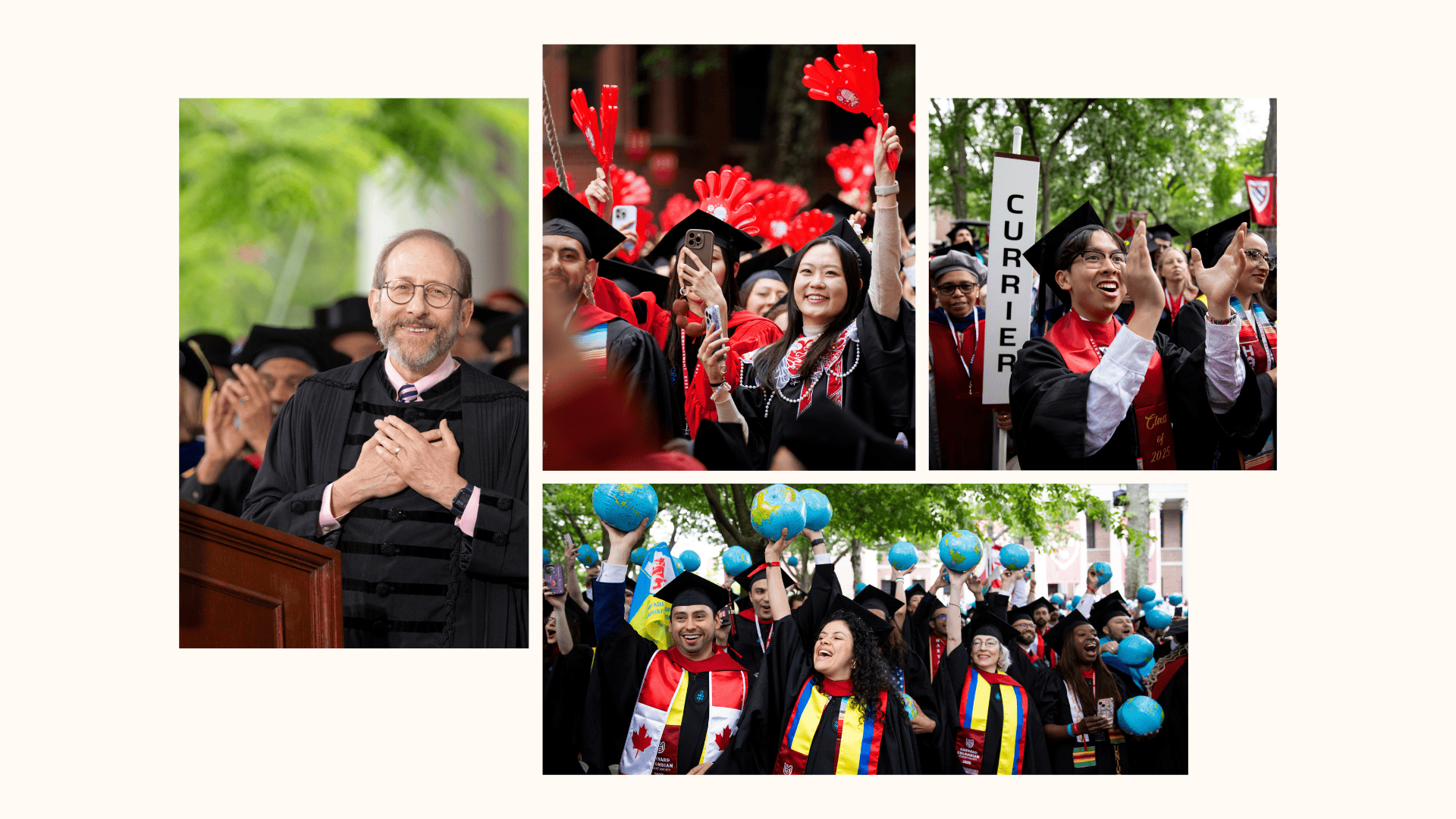

Proud day for Harvard

Photos by Niles Singer and Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographers; photo illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff Campus & Community Proud day for Harvard Harvard Staff Writers May 29, 2025 long read Joy, unity, and gratitude as University celebrates 374th Commencement Part of the Commencement 2025 series A collection of features and profiles

Proud day for Harvard

Photos by Niles Singer and Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographers; photo illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

Proud day for Harvard

Harvard Staff Writers

Joy, unity, and gratitude as University celebrates 374th Commencement

Part of the Commencement 2025 series

A collection of features and profiles covering Harvard University’s 374th Commencement.

All he got out was “Welcome,” before the crowd sprang to its feet to give a visibly moved President Alan Garber a standing ovation as he stood at the podium in the opening moments of Commencement. Across the Charles, University lawyers were presenting their case against a Trump administration move to block Harvard from enrolling international students. It was a graduation unlike others in its legal and political context but one that at its core remained deeply and distinctly personal. The blend of hope for the future, gratitude for family, friends, and teachers, and the poignancy of moving on were in evidence throughout the Yard. Here are some snapshots of the day.

Always remember: You might be wrong

In remarks to students, President Garber delivered a warning about the danger of getting too comfortable.

“The world as it is tempts us with the lure of what one might generously call comfortable thinking,” said Garber, “a habit of mind that readily convinces us of the merits of our own assumptions, the veracity of our own arguments, and the soundness of our own opinions, positions, and perspectives — so committed to our beliefs that we seek information that confirms them as we discredit evidence that refutes them.

“Though many would be loath to admit it, absolute certainty and willful ignorance are two sides of the same coin, a coin with no value but costs beyond measure. False conviction saps true potential. Focused on satisfying a deep desire to be right, we can willingly lose that which is so often gained from being wrong — humility, empathy, generosity, insight — squandering opportunities to expand our thinking and to change our minds in the process.”

Nearing the close of his address, he celebrated graduates as “the hope of this institution embodied — living proof that our mission changes not only the lives of individuals but also the trajectories of communities that you will join, serve, and lead.”

President Alan Garber processes into Tercentenary Theatre.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘Semper Veritas’

Early Thursday morning, tucked in a quiet, grassy nook in front of Holden Chapel, seniors gathered one last time to hear from Rakesh Khurana, the Danoff Dean of Harvard College.

In his final address to students before stepping down as dean, Khurana urged soon-to-be graduates to savor having reached such an important academic and personal milestone in their young lives.

“Enjoy this moment. Think of where you were four years ago, where you are today, and all that came in between, and embrace every second of this special day,” Khurana said.

He also urged students to use their time and talents to make positive contributions to the world. “Whatever your calling is in life, I encourage you to do good,” he said, later adding: “My fondest hope for all of you — that your education has helped prepare you to be good citizens and citizen leaders for our society. Go forth and make us proud.”

Khurana, who was named dean of the College in 2014, plans to return to the faculty of the Department of Sociology and Harvard Business School.

“I will miss you dearly, and it has been one of the greatest honors of my life to spend these last four years with you and to serve as dean of Harvard College,” he said. “Semper Veritas!”

Jean-Marie Alves-Bradford, M.D. ’92, and her son Malik Aaron Bradford III at Eliot House.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Opportunities and inspiration

More than three decades after her own Harvard graduation, Jean-Marie Alves-Bradford, M.D. ’92, beamed as her oldest son Malik Aaron Bradford III ’25 received his degree in biomedical engineering.

“I’m just so proud of him and it’s wonderful to see him accomplish this,” the former Kirkland House resident said. “This place has so many opportunities that he’s been a part of, and he’ll continue to grow from.”

She continued: “He’s really matured quite a bit. It’s been nice to see that evolution. He’s really settled and comfortable in his own skin.”

Alves-Bradford and her husband, Malik Bradford II, said they were excited for their son’s next steps. The new Harvard alumnus already has a job lined up after Commencement, the couple proudly shared. Bradford II shared his hope that Malik’s pursuits can be “applied in a way that’s going to help him feel fulfilled.”

A few feet away, fellow Eliot House parent Linda Erickson shared her excitement at seeing her daughter, Sarah Erickson ’25, accomplish her childhood dream.

Linda Erickson embraces daughter Sarah just after she received her degree.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

“When she was 8 years old, she told me, ‘I want to go to Harvard someday.’ So, to see that dream realized over all these years has been absolutely amazing,” Linda said. “She has pushed herself so hard to achieve that goal and to get to this day has just been inspirational.”

Sarah, who was homeschooled in Cincinnati by her mother before starting high school, received her undergraduate degree in biomedical engineering. At Harvard, she danced and performed in musical theater with the Harvard-Radcliffe Modern Dance Company and became a staff photographer for the Harvard Crimson.

“She’s not the same girl I dropped off four years ago,” Linda said. “She’s built great memories here with all the people she’s interacted with. It’s been amazing.”

Despite threats, hope for future of higher ed

“Honestly, it still doesn’t feel real,” said Jesse Hernandez, about moving on from life at Harvard. “I’m first-generation too, so there’s a part of me that has trouble imagining what comes next after something like this.”

The College graduate who studied economics, resided in Lowell House, and plans to hunt for a job in finance this summer, was especially grateful his parents and younger brother could make the rare trip from Florida to offer their support. “It feels good to be celebrating with all the people that helped me get here.”

With many close friends who are international students, Hernandez said he’s worried about their future after the Trump administration’s effort to block Harvard from enrolling them.

“Everybody’s nervous. Just when you start to think things can’t get worse,” they do, he said. Despite the circumstances, Hernandez said he’s trying to stay positive.

“I’ve got confidence that we’ll see this through, and that higher education won’t die today.”

Jubilant graduates fill Tercentenary Theatre.

Photo by Grace DuVal

3 years after knee tear, starting a new career

Danielle Ray’s journey to Harvard began with a knee injury. The professional squash player born in Calgary, Canada, had competed professionally since graduating from Cornell, but during the 2022 Canadian National Championships, she took an awkward step and tore her ACL, MCL, and meniscus all at once.

“It just got stuck on the floor as I was turning and just collapsed in,” she said.

Facing the prospect of multiple surgeries and many months out of the sport, Ray looked for something she could do in the meantime that could prepare her for the future. Her now-husband, who had graduated from Harvard with a master’s degree, suggested the Harvard Extension School.

A month later, Ray was enrolled in a master’s degree in information management systems. “I blew my knee out in June,” she said, “and I started the program in July.”

The program, Ray found, was a good mix of technical and policy-based courses. Her favorite course, “Fundamentals of the Law and Cybersecurity,” examined the legal, economic, and policy challenges that arise from cybersecurity threats. She found herself especially drawn to the policy components of the program and her work in agile project management — figuring out ways to solve dynamic, complex problems.

Because she could complete the degree online while taking one or two courses at a time, Ray could also move her life forward in other directions. She recovered from her surgeries, worked through physical therapy, and returned to the professional squash circuit — representing Canada at the international level. She competed in tournaments while pregnant and in January, gave birth to a baby girl.

Ray says she’s in a place right now “that’s a bit transitional.” She hopes to work herself into a policy-related position in the near future, building off interests she developed at Harvard. She still competes professionally.

But at Commencement Thursday with her family, she celebrated her accomplishment. “It’s almost three years to the day since I tore my knee,” she said. It would have been hard then to imagine all that would quickly follow.

Aidan Fitzsimons of Winthrop House said he paused his studies for several years before returning to Harvard. “I’m gonna miss this place,” he said.

Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

Giving disadvantaged Detroit youth a boost

“I didn’t see this for myself,” said Courtney Ebonique Smith, a newly minted graduate of the Harvard Extension School with a master’s degree in industrial-organizational psychology.

Smith grew up in foster care before being adopted and when she graduated from high school, she was living in a homeless shelter. Her experiences led her to start the Detroit Phoenix Center, a nonprofit in Detroit that provides housing, academic, and workforce support to young people who are experiencing housing insecurity and other barriers to opportunities.

“We provide them with support so they can thrive,” she said, “and maybe even come to Harvard.”

A few years after starting the nonprofit at the age of 25, Smith looked for ways to gain skills that she could immediately use as its CEO. She found the Extension School, which allowed her to take courses both on campus and from home.

In 2020, she started the Extension School’s Nonprofit Management Graduate Certificate. When she finished, she enrolled in a master’s degree. The flexibility of the program allowed her to work whenever she had time to spare. “I was able to do it at night, on the plane, in the morning, during the day,” she said, laughing. “It’s very convenient.”

Smith said that her skills in fundraising and project management improved after taking classes in both subjects. Overall, she said, the program taught her “how to be adaptable and to juggle a lot of things at once.”

Looking back, Smith is proud of the journey that led to her graduating from Harvard. “I want every person to know that it doesn’t matter where you come from,” she said. “There are opportunities for you to be able to live out the dreams that you have for your life and to thrive.”

Graduates pose in front of Widener Library.

Photo by Grace DuVal

A real team guy

Scott Woods II is a person of loyalties.

First on the list of the economics graduate is his House, Cabot.

“I’m a big quad guy — very loyal to the quad,” he said, while toting the Cabot House sign used in the Commencement Exercises across the Yard. “I boast about how great it is, even though it catches a lot of flak.”

Woods said Cabot, which is on the “quad,” is seen by some as less desirable than the other Houses, which are closer to the main campus along the Charles River. And he gets it because he started out that way.

“I remember it vividly,” he said of the moment he got his housing assignment as a first-year. “You could hear a pin drop — no one was excited about it at first. But then as soon as we got out there, we just realized it was all a myth, and we had to make it what it was, which was a good time.”

Besides being a Cabot House booster, Woods is also a Crimson football loyalist, having been a wide receiver on the team.

“Harvard came in with a last-minute offer that changed my life. And since I committed to play here, my life has been on the upward trend,” he said.

Woods said he’s off to the University of Maine next year, where he’ll pursue an M.B.A. Originally from Virginia, he said in all seriousness that Cabot helped make Harvard home.

“The people in Cabot made me feel seen and made me feel comfortable. It made me feel like I had a family,” he said, grinning. “Being all the way out here you don’t really have too many people to interact with.”

Woods was joined on Commencement Day by his mom, dad, brother, and two grandmothers. He said they were proud of their Cabot House mascot.

“They thought I was the man. They wanted to get a picture with me,” he said.

Maryam Hussaini (center) cheers as her group of graduate students is recognized during the Commencement Exercises.

Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘It’s surreal’

Jean Filo hustled to meet his parents after the Commencement ceremony, part of a departing wave of other Medical School graduates identifiable by the stethoscopes they wore along with their caps and gowns.

He paused for a moment to reflect on what his graduation meant not only to himself as an immigrant from Syria but also to his parents waiting eagerly to hug their son.

“It’s surreal,” he said. “Today is mostly about my parents and them enjoying this.”

During his time at Harvard Medical School, Filo worked in cerebrovascular research at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center’s Brain Aneurysm Institute. He said he’s now heading off to Philadelphia to do a residency in neurosurgery.

But first, he said, rushing off, he had dinner plans with the parents.

Family pride — and impact

Caroline Maynes and Sierra Dorweiler have been watching their son and brother, respectively, for years, and, though they know him well, they’re still impressed. Nicholas Maynes, who graduated with a master’s degree in public administration on Thursday, has been on a yearslong journey that has taken him to war and back.

As the pair watched the Commencement unfold in Tercentenary Theatre, they said that Maynes has been entirely self-driven, starting with his education at West Point.

His Army service as a field artillery officer included deployment to Iraq during the liberation of Mosul. After that, he earned a master’s degree in business administration at the University of California at Berkeley before enrolling at Harvard to study at the Kennedy School.

“Academics has just been his passion,” said Caroline.

Watching her brother couldn’t help but have an impact on her, Dorweiler said. Maynes has always encouraged her to focus on what can be done, not what can’t, she added.

“I’m so proud because he’s been the one who’s pushed me to achieve academically,” she said. “He just makes it seem like pretty much anything is possible.”

Her goal: To help as many people learn as she can

Growing up in India, Devina Neema — who graduated Thursday from the Harvard Graduate School of Education — observed a major disparity between private and public schools. Her school had good classrooms and teachers and 40 hours of class every week. In public schools, students could get four or five hours of instruction, with few books and limited interaction between teachers and parents.

After graduating from college, Neema began teaching in public schools through a nonprofit program. The conditions weren’t ideal. At times, she led classrooms filled with 90 students. “It was a new world for me,” she said. “I realized this is where education needs to happen and get better.”

For different nonprofits, Neema worked across rural and urban areas to understand how students learned at different types of schools. How did they learn their first language? What were the math disparities? Were there any technological solutions?

To explore those questions more thoroughly, and to get a more formal education in teaching and how to change education at a systemic level, Neema looked to the HGSE’s master’s program in Learning Design, Innovation, and Technology.

At Harvard, Neema explored how people of different ages learn and how technology can augment it. She also studied how learners can develop transferable skills, such as social skills, and apply them to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

Having never formally studied education in a university setting, she was struck — and inspired — by the sheer amount of research her professors performed in their areas of expertise. “If you have to truly understand something at heart,” she said, “then you have to broaden your perspective but also narrow down your niche and go deep.”

With her program now complete, Neema plans to stay in the area so she can continue to learn and “build something here,” she said. After studying the education systems in many countries and the workings of international and humanitarian aid, she wants to help as many people learn as she can — with any tools she has.

Sheriff of Middlesex County Peter J. Koutoujian leads the processional into Harvard Yard.

Photo by Grace DuVal

What’s to come

Like many, College seniors Kylie Hunts-in-Winter and Taylor Larson weren’t quite sure what to expect from Morning Exercises on what is typically a joyful day.

Given the tensions sparked by Harvard’s legal battles with the Trump administration, they weren’t certain how graduating students would respond to University officials or the celebration.

“Some people were saying on [the social media app] Sidechat that they want to cheer for [President Alan] Garber, and other people. And so, I’m interested to see how this plays out,” said Hunts-in-Winter, a champion martial artist who studied sociology and Ethnicity, Migration, Rights.

The duo stood with Larson’s Adams House colleagues as undergraduates prepared to process into Tercentenary Theatre. Not long after, Garber and other University officials received robust cheers from the assembled crowd as they made their way toward the stage.

For Larson, a history and literature concentrator from Minnesota, the morning was one of conflicting emotions. While it was “exciting,” she confessed to also feeling “overwhelmed by everything that’s to come after this.”

Both identify as first-generation, low-income students. Larson plans to pursue a master’s degree in history in London, while Hunts-in-Winter, whose family is Lakota from the Standing Rock Reservation, intends to remain in the Boston area to pursue public service work with Native American communities.

“I am glad and I’m very grateful for my time,” said Larson. “I met all my best friends here and had a lot of opportunities because of Harvard funding.”

Dunster House ceremony: Lasting friendships

Residents of Dunster House returned to their home of the last three years to gather with parents, grandparents, siblings, and friends, receive degrees, enjoy lunch — and let it all sink in.

Graduate Minsoo Kwon, a Mather House resident, was at Dunster to celebrate her friend Hannah Ahn, whom she met five years ago during a gap year in Korea.

Kwon said the two, who have remained friends throughout college, will both be heading off to law school in the fall — with plans already in the works for frequent visits.

“I’ll be at Yale, and Hannah will be at Columbia,” she said. “Still along the Amtrak line.”

Ahn earned a degree in government while Kwon got hers in neuroscience. She’s interested in drug and healthcare policies that overlap law and science.

Sara Silarszka receives her diploma at Dunster House.

Photo by Grace DuVal

Two other friends sharing in the afternoon festivities were Sara Silarszka and Quincy Brunner Donley — first-year roommates who got along so well they stayed together for the next three years at Dunster.

“We were in a double for three years together, and so this is the first year we had our own rooms,” Donley said.

Asked whether they missed sharing the close quarters, Donley said, “I think I did,” followed by a quick “definitely” by Silarszka.

Both roommates made their mark in Harvard athletics — Silarszka, as a field hockey player, now with a degree in integrated biology, and Donley, a Nordic skier with a degree in economics.

Donley said after graduation, she’s moving back to her home state of Alaska to pursue professional skiing.

“At least for the foreseeable future,” she said.

Silarszka, who grew up in Virginia, said she is hoping to visit her old roomie. And she’s taking a gap year before applying to medical school.

“I just love living with my best friends,” she said. “You’ll just never be this close to so many people you love, so that’ll be hard to leave behind.”

Graduates entering Tercentenary Theatre.

Photo by Grace DuVal

Back to the beginning

Chidimma Adinna, a graduating senior from Adams House, left Nigeria at age 6 when her parents immigrated to California. Now she’s set to return, thanks to a fellowship to teach at a high school some of her family members still attend.

While her desire to return to Nigeria stems from her family history, the how and why owe largely to her studies at Harvard. A psychology concentrator, Adinna became interested in climate change during her time as an undergrad. As a fellow in Nigeria, she plans to promote sustainability and help the school take steps to fight the climate crisis. She’ll also act as a tutor and mentor students who want to go to college.

“Since I was younger, I was always trying to be connected to my community in Nigeria,” she said. “This has involved me donating clothes through organizations that I founded with my family, and it’s a mission that I’m trying to continue, even postgrad. It’s been evolving over the years I’ve been trying to give back to my community.”

Connecting flights?

Justin Biassou spent a lot of time in an airplane cabin on the way to his master’s degree.

Starting in 2022, he would occasionally commute from Seattle to Cambridge for in-person classes from Harvard Extension School, where he earned an A.L.M. in international relations.

But Biassou is comfortable in the air. He started flight training at 12 and got his private pilot’s license at 17. Even as he studied, he was working full time leading an air safety team for the Federal Aviation Administration.

Biassou took up his coursework in January 2022, when the COVID-19 pandemic still loomed over campuses, classrooms, and airports.

“I took one class per semester, and each one had this incredible group of students with all these different backgrounds — often they were working, too.”

Many of Biassou’s courses did take place online. But person-to-person time in Cambridge was well worth the flight, as were a few intensive January courses crammed into his time off from work.

At a time when “a lot of us just felt isolated, and very uneasy,” Biassou recalled, class “just really brought a lot of us together … These have become lifelong friends.”

The Extension School allowed Biassou a chance to expand his skill set in aviation safety. With new expertise in international relations, he hopes to “harmonize” safety efforts beyond U.S. borders, with authorities like the United Nations and the International Civil Aviation Organization.

His three-year, transcontinental balancing act may have earned Biassou “a lot of gray hairs.”

“But I had a really incredible support system: my significant other Michelle, my parents, my sisters,” Biassou said, as his family stood by. “They allowed me to focus on the things that needed to get done: Yes, 40 hours a week keeping aviation safe, then also working on my classes.”

Makena Tenpenny (center) embraces her fellow Harvard Graduate School of Education classmates as their class is recognized.

Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

A child of immigrants gives back

Many faculty and graduates at Commencement ceremonies wore stickers, flowers, and other symbols in support of Harvard’s international students — now facing threats from the Trump administration.

For Daniel Roque-Coplín, J.D. ’25, the cause of safeguarding the rights of newcomers in America is personal — and the focus of his professional goals.

“Both of my parents are immigrants: My mom is from the Dominican Republic; my dad is from Cuba,” Roque-Coplín said, as he and his mother huddled before lunch. “They never in their lives dreamed that their son could go to a school like this one.”

His law school journey was not always easy — particularly at the beginning.

“First year, second year, you spend a lot of time in the library,” he said. “A lot of times, the studying can consume you, because you’re competing with everyone else, in a sense.”

Roque-Coplín said he was driven by a desire to help families like his own, with immigrant pasts and big ambitions in the United States.

Even before the latest tightening of immigration law and enforcement, the law did not always serve those families well, Roque-Coplín said.

He hopes to change that.

“Immigration law is intersectional, right? There are public-health needs, criminal needs, straightforward needs” related to legal status and asylum.

He had already begun that work in Cambridge as a student attorney in family practice with the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau, which offers free representation to low-income clients in Greater Boston.

Roque-Coplín acknowledged that he enters the legal professional at an acutely difficult moment for the families he hopes to serve. But he and other Law School graduates said they see that field as a chance to do urgent work.

“Through the grace of God, I’ve overcome — I’m here,” Roque-Coplín said. About the fights to come, “I’m nervous, I’m excited, and I feel, honestly, like nothing can stop me.”

Graduates wait to receive their diplomas at Lowell House.

Photo by Grace DuVal

A star’s turn

As the official ceremonies of Commencement Day wound down, families gathered on the steps of Widener Library for photographs with their graduates.

Elio Kennedy-Yoon showed particular patience with the many iterations of family pictures on offer: his three siblings, separately and together; his father, then grandfather; his girlfriend; then the whole clan together.

You might credit Kennedy-Yoon’s recent experience with celebrity, as an actor and singer in Din & Tonics, the College a capella group. Just last year, he made a splash online with a viral solo version of Barry Manilow’s “Copacabana.” Fan art, mashups, and the group’s world tour ensued.

After Commencement, Kennedy-Yoon wore two sashes: one honoring his Asian American heritage and another for LGBT pride.

Even before that viral moment, the last five years have been transformative for Kennedy-Yoon.

First, a gender transition during the pandemic, and a jarring move from Utah to Cambridge.

“I love Utah, but the people can be very conservative. I really found a community here that’s very accepting, very diverse.” (Among that community was Kennedy-Yoon’s girlfriend, a few years older — and “the love of my life,” he said with a smile.)

Still, as a queer Asian American with some online visibility, it hasn’t been possible to dodge hostility or derision. When Donald Trump was elected president the first time, Kennedy-Yoon was 13. In this tumultuous spring, he said it feels like a long time to have lived in conflict with the country’s political leadership.

That has made the University’s resistance to Trump administration mean all the more.

“In a weird way. I’ve never been prouder to be a Harvard student than right now,” Kennedy-Yoon said. “That we’re standing up for academia, for knowledge, for truth … and against tyranny.”

Ready to start

When Annabeth Tao was an undergraduate at UCLA, she worked as a research assistant for a professor focused on computer game animation. In her year at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, she added to that experience a better understanding of how students learn, which she plans to blend into a startup focused on devising interactive games to help students become more creative in STEM studies.

When she arrived on campus in the fall, enrolled in the Ed School’s Learning Design, Innovation, and Technology master’s degree program, Tao had a vague plan to use the arts to enhance education. Over the course of her studies, she refined that ambition, in part through conversations with fellow students. In fact, some of her best memories of her time at Harvard are the brainstorming sessions with classmates.

She’ll have to find a job while getting the startup off the ground, but said that she’s excited about the chance to help unleash creativity among students and teachers, shaping “a dynamic learning experience for kids.”

-

Harvard Gazette

-

Judge sides with Harvard on international students

Nation & World Judge sides with Harvard on international students Photo by Dylan Goodman Alvin Powell Harvard Staff Writer May 29, 2025 3 min read Extends order blocking government’s attempt to revoke participation in Student and Exchange Visitor Program A federal judge on Thursday extended a temporary restraining order blocking the Trump administration from terminating Harvard’s rig

Judge sides with Harvard on international students

Judge sides with Harvard on international students

Photo by Dylan Goodman

Alvin Powell

Harvard Staff Writer

Extends order blocking government’s attempt to revoke participation in Student and Exchange Visitor Program

A federal judge on Thursday extended a temporary restraining order blocking the Trump administration from terminating Harvard’s right to host international students and scholars. The restraining order was issued last week after the University sued in response to an attempt by the government to revoke Harvard’s Student and Exchange Visitor Program certification.

More than 5,000 international students and scholars at Harvard are at risk of losing legal status due to the revocation order, which was first conveyed in a letter from Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem and has sown fear and confusion among international students and scholars at Harvard and other universities. In its lawsuit, Harvard argues that the government’s actions violate the First Amendment, the Due Process Clause, and the Administrative Procedure Act. President Alan Garber has described the Trump administration’s efforts as retaliatory.

Responding Thursday to Judge Allison Burroughs’ decision to extend the temporary restraining order, the University noted the contributions of international students and scholars and pledged to continue to fight for its ability to welcome them to campus.

“Harvard will continue to take steps to protect the rights of our international students and scholars, members of our community who are vital to the University’s academic mission and community — and whose presence here benefits our country immeasurably,” a University spokesperson said.

The extension of the restraining order came as students, staff, and faculty celebrated Commencement in Harvard Yard. Garber received a standing ovation when he began welcoming remarks that included a nod to the University’s global community.

“Welcome members of the Class of 2025 — members of the Class of 2025 from down the street, across the country, and around the world,” he said, adding: “Around the world just as it should be.”

Elsewhere in the Yard and around campus, students, alums, and others welcomed Harvard’s success in court.

International students are “part of what makes Harvard one of the best universities in the world,” said Kevin Pacheco, an instructor at the Medical School. Caleb Thompson ’27, co-president of the Harvard Undergraduate Association, agreed.

“I’m obviously very happy about the news,” Thompson said. “International students are a part of all our lives. I’m not the first person to say this, but Harvard isn’t Harvard without international students … these are some of the most talented, intellectually capable students on our campus.”

He added: “For me it’s personal even though I’m a domestic student: I have eight international suitemates. They’re the most important people in my life.”

Sy Boles of the Harvard Staff contributed to this report.

-

Harvard Gazette

-

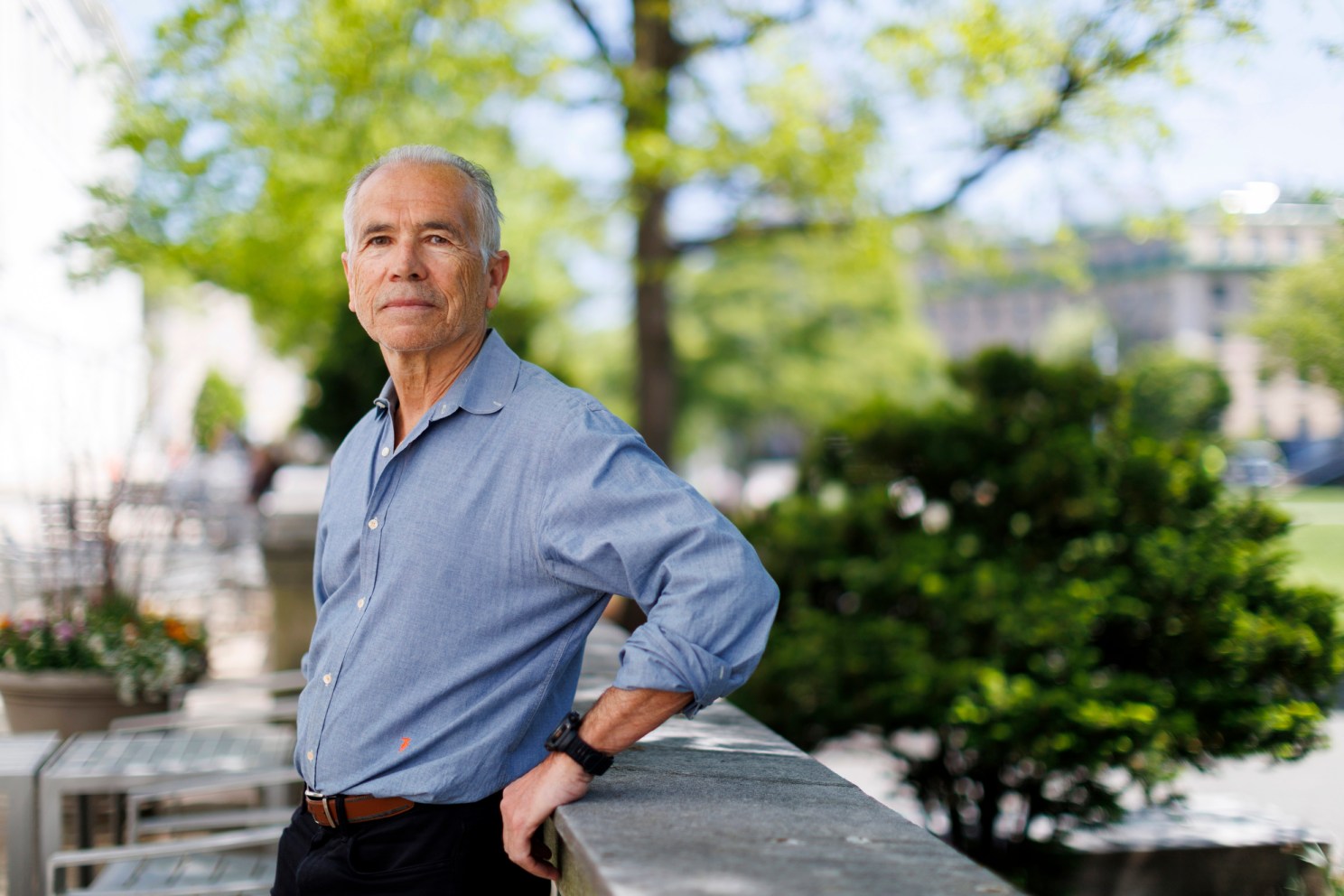

Verghese tells an American story at Commencement

Campus & Community Verghese tells an American story Photo by Grace DuVal Liz Mineo Harvard Staff Writer May 29, 2025 5 min read Physician-writer foregrounds immigrants’ contributions to Harvard and the nation, urges graduates to show courage, character in face of hardship Part of the Commencement 2025 series A collection of features and

Verghese tells an American story at Commencement

Verghese tells an American story

Photo by Grace DuVal

Liz Mineo

Harvard Staff Writer

Physician-writer foregrounds immigrants’ contributions to Harvard and the nation, urges graduates to show courage, character in face of hardship

Part of the Commencement 2025 series

A collection of features and profiles covering Harvard University’s 374th Commencement.

Abraham Verghese underscored the vital role of immigrants in the life of the nation at Harvard’s 374th Commencement Thursday at Tercentenary Theatre. He was speaking from experience.

Born in Ethiopia to expatriate teachers from India, Verghese, a doctor and writer, began his medical studies in Addis Ababa but had to interrupt them as the country descended into civil war in 1974. After completing his medical studies at Madras Medical College in India, he arrived in Johnson City, Tennessee, as an infectious disease specialist in the mid-1980s, the early days of the AIDS epidemic.

Verghese, who teaches at Stanford, was the principal speaker at Commencement, which unfolded as a federal judge in Boston extended a temporary restraining order blocking the Trump administration’s revocation of Harvard’s ability to host international students and scholars. That action and others by the government were on Verghese’s mind as he delivered a passionate defense of immigrants and international students living, studying, and working in the U.S.

“When legal immigrants and others who are lawfully in this country, including so many of your international students, worry about being wrongly detained and even deported, perhaps it’s fitting that you hear from an immigrant like me,” he said.

He also spoke directly to the contributions of foreign-born doctors at hospitals across the country.

“We were recruited here because American medical schools simply don’t graduate sufficient numbers of physicians to fill the country’s need,” said Verghese, who spent two years early in his career at what is now Boston Medical Center. “More than a quarter of the physicians in the country are foreign medical graduates, many of them ultimately settling in places that others might not find as desirable.

“A part of what makes America great, if I may use the phrase, is that it allows an immigrant like me to blossom here, just as generations of other immigrants and their children have flourished and contributed in every walk of life, working to keep America great.”

Pointing to his experience as a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop — his books include “Cutting for Stone,” “My Own Country,” and “The Covenant of Water” — Verghese credited America for enriching his life as an author. He quoted the novelist E.L. Doctorow: “It is the immigrant hordes who keep this country alive, the waves of them arriving year after year. Who believes in America more than the people who run down the gangplank and kiss the ground?”

He also praised Harvard President Alan Garber for resisting Trump administration demands for viewpoint audits and other measures, even as dramatic funding cuts imperil the University’s ability to carry out its research mission. Harvard deserves support and praise, he said, for “affirming and courageously defending the essential values of this university, and indeed of this nation.”

Closing his remarks, Verghese offered a few pieces of advice to the Class of 2025. First, he urged students to read fiction, because novels offer “powerful lessons about life” and can open a reader’s mind to unfamiliar lives and experiences. He was inspired to become a doctor in part by reading W. Somerset Maugham’s “Of Human Bondage,” he recalled.

“If you don’t read fiction,” Verghese said, “my considered medical opinion is that a part of your brain responsible for active imagination atrophies.”

Verghese also stressed the importance of character and courage: “Graduates, the decisions you will make in the future under pressure will say something about your character, while they also shape and transform you in unexpected ways. Make your decisions worthy of those who supported, nurtured, and sacrificed for you: your parents, your partners, your family, and your ancestors. Make your decisions worthy of this great university and the hardship it must endure going forward as it works to preserve the value of what you accomplished here.”

Lastly, drawing on the lessons he learned from AIDS patients he tended to Tennessee in the mid-1980s, Verghese asked students to take great care with the gift of time. Seeing men in their 30s and 40s face death was heartbreaking, he said, but he found comfort in the fact that many of them, at the end of their lives, cherished the company of family.

“They found that meaning at the end of a shortened life did not reside in fame, power, reputation, money, or good looks,” he said. “Instead, they found that meaning in their lives ultimately resided in the successful relationships they had forged in a lifetime, particularly with family.”

Verghese read to the crowd a letter he had shared many times before. In it, a young man dying of AIDS assures his mother that, having fulfilled many of his dreams, he has no regrets, and is grateful that his illness has allowed him to slow down to spend time with his family.

“I’ve enjoyed a life full of adventure and travel, and I loved every moment of it. But I probably never would have slowed down enough to really appreciate all of you if it hadn’t been for my illness. That’s the silver lining in this very dark cloud …

“If anyone ever asks you if I went to heaven, tell them this: I just came from there. No place could conceivably be as wonderful as where I’ve spent these last 30 years. I’ll miss it. I’ll miss you, mother. I’m so glad we made good use of this time to get to know each other again.”

After reading the last lines, Verghese exhorted students, “Cherish this special day. And above all, make good use of your time.”

-

University of Mellbourne

-

Applications Open for Atlantic Fellows for Social Equity 2026 Cohort

The Atlantic Fellows for Social Equity (AFSE) has opened applications for the 2026 cohort, seeking changemakers from Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand and Pacific Island nations.

Applications Open for Atlantic Fellows for Social Equity 2026 Cohort

The Atlantic Fellows for Social Equity (AFSE) has opened applications for the 2026 cohort, seeking changemakers from Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand and Pacific Island nations.

-

Princeton University

-

Margaret Martonosi named University Professor at Princeton

Margaret Martonosi is a leading researcher in computer architecture and hardware design. University Professor is Princeton’s highest honor for faculty.

Margaret Martonosi named University Professor at Princeton

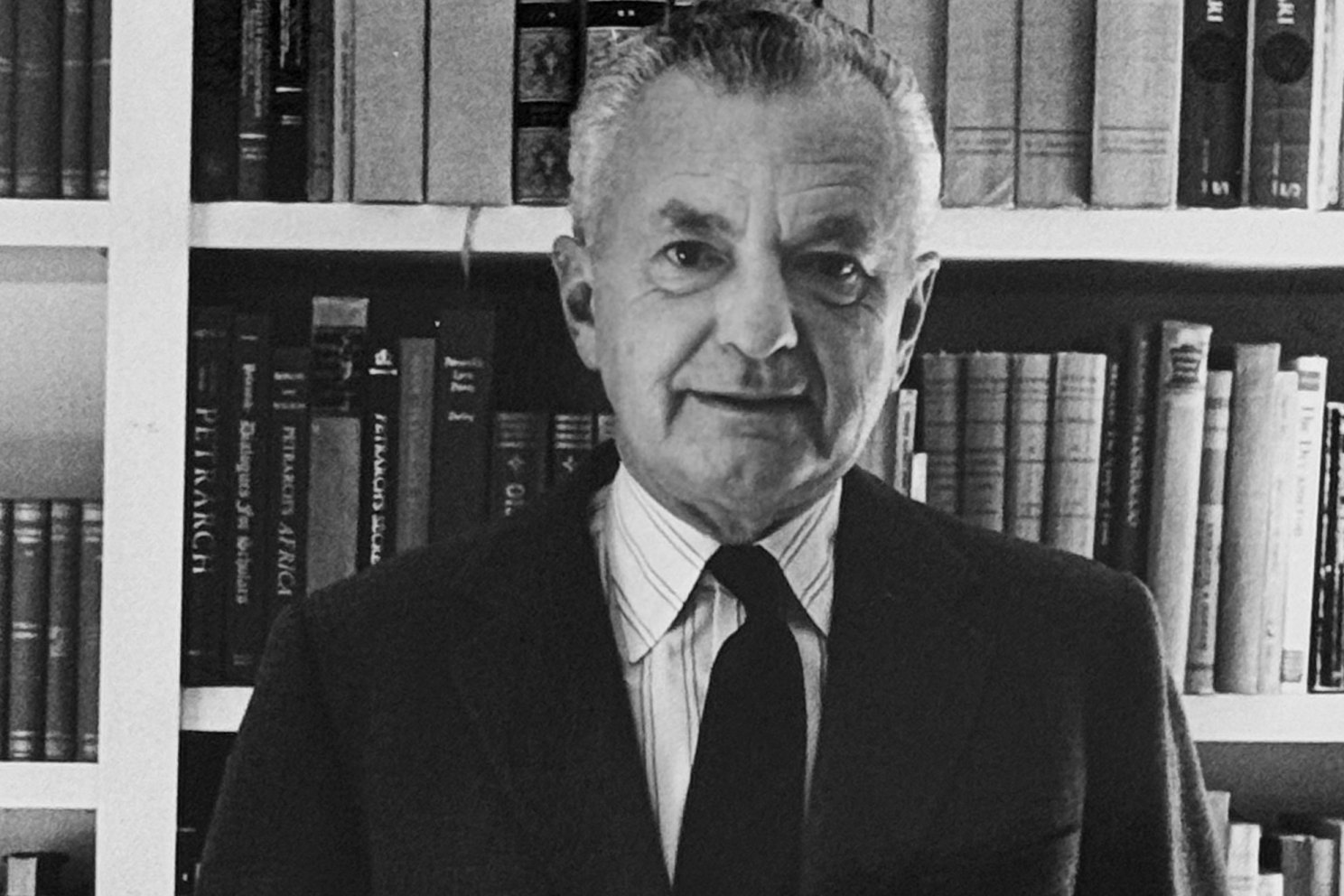

Remembering Sunney Chan (1936–2025)

-

Harvard Gazette

-

Kannon Shanmugam to join Harvard Corporation

Campus & Community Kannon Shanmugam to join Harvard Corporation Kannon K. Shanmugam.Gittings Global Photography May 29, 2025 5 min read Alumnus of College and HLS elected to University’s senior governing board Kannon K. Shanmugam ’93, J.D. ’98, a prominent and prolific appellate attorney and alumnus of Harvard College and Harvard Law School, will join the Harvard Corporation as its newest member, t

Kannon Shanmugam to join Harvard Corporation

Kannon Shanmugam to join Harvard Corporation

Kannon K. Shanmugam.

Gittings Global Photography

Alumnus of College and HLS elected to University’s senior governing board

Kannon K. Shanmugam ’93, J.D. ’98, a prominent and prolific appellate attorney and alumnus of Harvard College and Harvard Law School, will join the Harvard Corporation as its newest member, the University announced on Thursday. Shanmugam will succeed Theodore V. Wells Jr., J.D. ’76, M.B.A. ’76, who departs the board after 12 years of service.

Citing his “deep devotion to Harvard and to the importance of academic values and academic freedom,” President Alan Garber and Senior Fellow Penny Pritzker announced Shanmugam’s election in a message to the Harvard community on Thursday afternoon.

“Kannon Shanmugam is one of the nation’s most accomplished and admired appellate attorneys, who has also served an array of educational institutions,” said Garber and Pritzker. “Beyond his extensive experience counseling and representing major organizations in complex matters, he is known for his intellectual acuity and curiosity, his remarkable work ethic, his warm and collegial manner, his adroitness in engaging people with varied points of view, and his commitment to academic excellence.”

Shanmugam has argued 39 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court and more than 150 other appeals in courts across the country, including all 13 federal courts of appeals and numerous state courts. Formerly a partner at the law firm Williams & Connolly and a member of the Office of the Solicitor General in the Department of Justice, Shanmugam is now a partner at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, where he is also the founding chair of the firm’s Supreme Court and Appellate Litigation Practice, chair of its office in Washington, D.C., and co-chair of the Litigation Department.

Shanmugam has also served a number of educational institutions in advisory and governance roles, including as past chair of the board of trustees of Thurgood Marshall Academy, a public charter high school in Washington, D.C.; current trustee of both the American School of Classical Studies at Athens and the University of Kansas Endowment; and past trustee of the Association of Marshall Scholars.

“It’s an honor to have been asked to serve on the Harvard Corporation, and I look forward to contributing my perspective to the Corporation’s deliberations in the coming years,” said Shanmugam. “My reason for agreeing to serve is simple: I owe everything to Harvard. Harvard gave me opportunities I never would have had, and it exposed me to different people and new ideas.

“Harvard has gone through difficult times and faces substantial challenges, but it does so much good for the world,” he continued. “Harvard is one of our nation’s most important institutions, and when an institution has problems, I believe the solution is to work constructively to fix the problems, while holding true to its foundational commitment to academic excellence. I look forward to doing my part to help Harvard meet those challenges and to make the University a better, stronger place for the future.”

A native of Kansas, Shanmugam’s father was a professor of electrical engineering at the University of Kansas after his parents emigrated from India. In 1993, Shanmugam graduated summa cum laude from Harvard College, where he concentrated in classics and served as editor in chief of the Harvard Independent. He studied as a Marshall Scholar at Oxford, where he received a Master of Letters degree in classical languages and literature. Shanmugam was executive editor of the Harvard Law Review before graduating magna cum laude from Harvard Law School in 1998.

After law school, Shanmugam clerked for Judge J. Michael Luttig of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit and for Justice Antonin Scalia of the Supreme Court. He entered private practice as an associate at Kirkland & Ellis and later served as assistant to the solicitor general in the Department of Justice from 2004 to 2008.

Shanmugam practiced as a partner at Williams & Connolly for more than a decade after leaving the solicitor general’s office, rising to become one of the country’s most sought-after appellate lawyers. He served as co-chair of the American Bar Association’s Appellate Practice Committee and as the president of the Edward Coke Appellate Inn of Court — an organization dedicated to advancing the rule of law through example, education, and mentoring. Shanmugam is the only practicing American lawyer who is an honorary bencher of the Inner Temple, one of the four English Inns of Court. He has also taught Supreme Court advocacy at Georgetown University Law Center and is an elected member of the American Law Institute and a Federalist Society contributor.

One of six appellate lawyers ranked as a Star Individual by Chambers USA, Shanmugam was a finalist for The American Lawyer’s Litigator of the Year in 2022 and 2024, and he was named Appellate Litigator of the Year by Benchmark Litigation in 2021.

In accordance with the University’s charter, Shanmugam was elected by the members of the Corporation with the consent of the University’s Board of Overseers. He will begin his service on July 1 as Wells departs the board. Garber and Pritzker thanked Wells and noted his service in their message to the community.

“We owe profound gratitude to our colleague Ted Wells, who since 2013 has served the Corporation and the University superbly with his powerful mind, his formidable legal expertise, his strong commitment to academic ideals and principled decision-making, and his humane concern for others,” said Garber and Pritzker. “In Kannon Shanmugam, we are fortunate to have someone well positioned to carry forward and build on Ted’s remarkable legacy, while bringing fresh perspectives and valuable insights to the hard and important work ahead.”

The Harvard Corporation, formally the President and Fellows of Harvard College, was chartered in 1650 and exercises fiduciary responsibility with regard to the University’s academic, financial, and physical resources and overall well-being. Chaired by the president, the 13-member Corporation is one of Harvard’s two governing boards. Members of Harvard’s other governing board, the Board of Overseers, are elected by holders of Harvard degrees.

Stanford Alumni Association awards recognize outstanding students

-

Stanford University

- Secretary of Energy Chris Wright visits SLAC to explore groundbreaking innovations

Secretary of Energy Chris Wright visits SLAC to explore groundbreaking innovations

Stephen Breyer says it’s up to today’s students to preserve the rule of law

Meet Khoi Young, ’25

‘The current strategy for dealing with drug resistance is like Whac-A-Mole’

Stanford streamlines the process of faculty appointments and promotions

Five things to do in virtual reality – and five to avoid

Student-led hub connects law students with immigration and human rights work

-

ETH News

-

Save twice the ice by limiting global warming

A new study with ETH Zurich, finds that if global warming exceeds the Paris Climate Agreement targets, the non-polar glacier mass will diminish significantly. However, if warming is limited to 1.5°C, at least 54 per cent could be preserved—more than twice as much ice as in a 2.7°C scenario.

Save twice the ice by limiting global warming

-

Cornell University

-

Study: Tech can empower home care workers, not just surveil them

A team of Cornell researchers is exploring how workplace tracking apps can be used not to surveil workers, but to help them build solidarity and improve their working conditions.

Study: Tech can empower home care workers, not just surveil them

-

Harvard Gazette

-

‘Like we’re reaching a new period of human history’

Campus & Community ‘Like we’re reaching a new period of human history’ Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer Nikki Rojas Harvard Staff Writer May 29, 2025 4 min read Fascination with artificial intelligence pulls Muqtader Omari back to his scholarly first love: Science Part of the Commencement 2025 series A collection of features and p

‘Like we’re reaching a new period of human history’

‘Like we’re reaching a new period of human history’

Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

Nikki Rojas

Harvard Staff Writer

Fascination with artificial intelligence pulls Muqtader Omari back to his scholarly first love: Science

Part of the Commencement 2025 series

A collection of features and profiles covering Harvard University’s 374th Commencement.

Growing up in Afghanistan, Muqtader Omari ’25 loved astrophysics, but the political climate of his country led him on a couple of detours — working as a writer and studying government — before he ultimately returned to his scientific roots to focus on artificial intelligence.

After he graduated from high school in Kabul, Omari launched a nonprofit called Talk Science, which aimed to educate young people on social media platforms. But he soon found education had political dimensions he hadn’t anticipated.

“I started noticing all these limitations that exist and was interested in learning more about where these came from,” said Omari, pointing to the barriers faced by Afghan girls seeking an education under Taliban rule. His curiosity led him to write for a newspaper in Kabul, and eventually to pursue higher education in the U.S.

At Harvard, where he is one of nearly 6,800 international students across the University, Omari opted to concentrate in government and in computer science. Throughout his undergraduate years, he sought to learn more about his birth country as the Taliban retook control of Afghanistan’s government. In 2023, the Adams House resident met lecturer in the Modern Middle East Mohammad Sagha through a course dedicated to regional order, U.S. wars, and the politics of Iraq and Afghanistan.

“What makes Muqtader unique is that while he has a compelling personal story, he never relied on that to solely inform his worldview,” said Sagha. “He’s intellectually rigorous and tries to objectively study and understand Afghanistan, its neighboring environment, U.S. foreign policy, and other factors through a balanced scholarly lens — that is rare to find.”

Sagha added: “He is very passionate about what is happening in his country and is eager to make a difference.”

“I preplanned a lot of my life in high school, and none of it worked out. I’ll let myself decide in the moment. I just hope I’m happy and I’m learning.”

Omari’s early intellectual leanings may have been with Afghanistan, but he was determined to push himself to meet students from all walks of life. About filling out his first-year roommate survey, Omari said, “I didn’t want to be with other international or Middle Eastern students. I wanted it to be as opposing to who I am as possible, because that’s what I thought Harvard was all about.”

He joined the Institute of Politics as a study group leader and the John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum Committee, where he assisted in the production of nonpartisan dialogues on politics, public service, and other affairs. But halfway through his four years, Omari realized that politics wasn’t for him. Missing the rigidity that science offered, he became fascinated with artificial intelligence.

“It’s mind-boggling to me,” he said. “It feels like we’re reaching a new period of human history.”