5 faculty members named Harvard College Professors

5 faculty members named Harvard College Professors

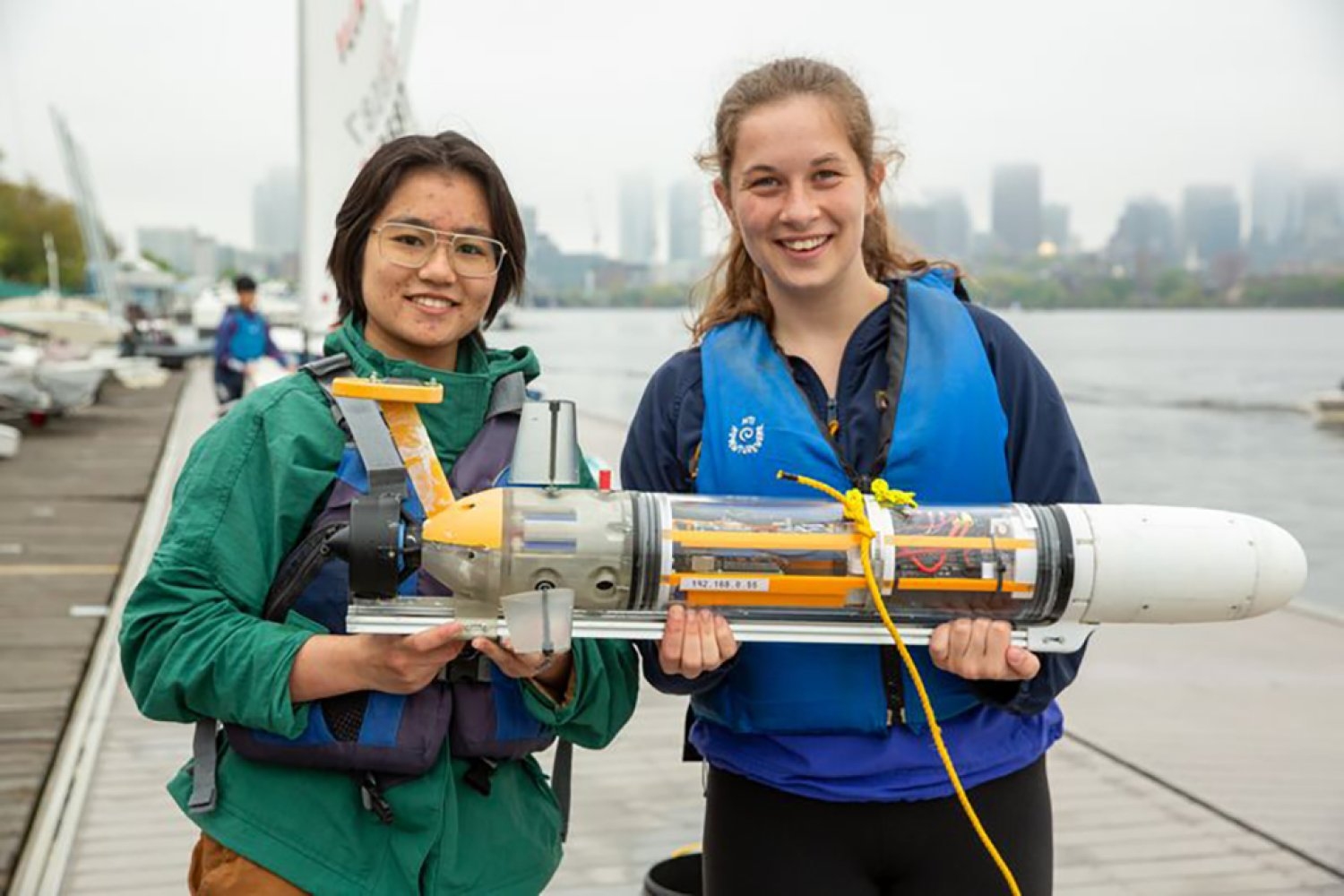

File photos by Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer, Grace DuVal, and Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer; photo illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

Eileen O’Grady and Kermit Pattison

Harvard Staff Writers

Recognized for excellence in teaching in fields ranging from geometry to politics

Five faculty members have been awarded a Harvard College Professorship for excellence in undergraduate teaching, in fields ranging from high-dimensional geometry to comparative politics. Hopi Hoekstra, Edgerley Family Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, announced the recipients on May 6. They are:

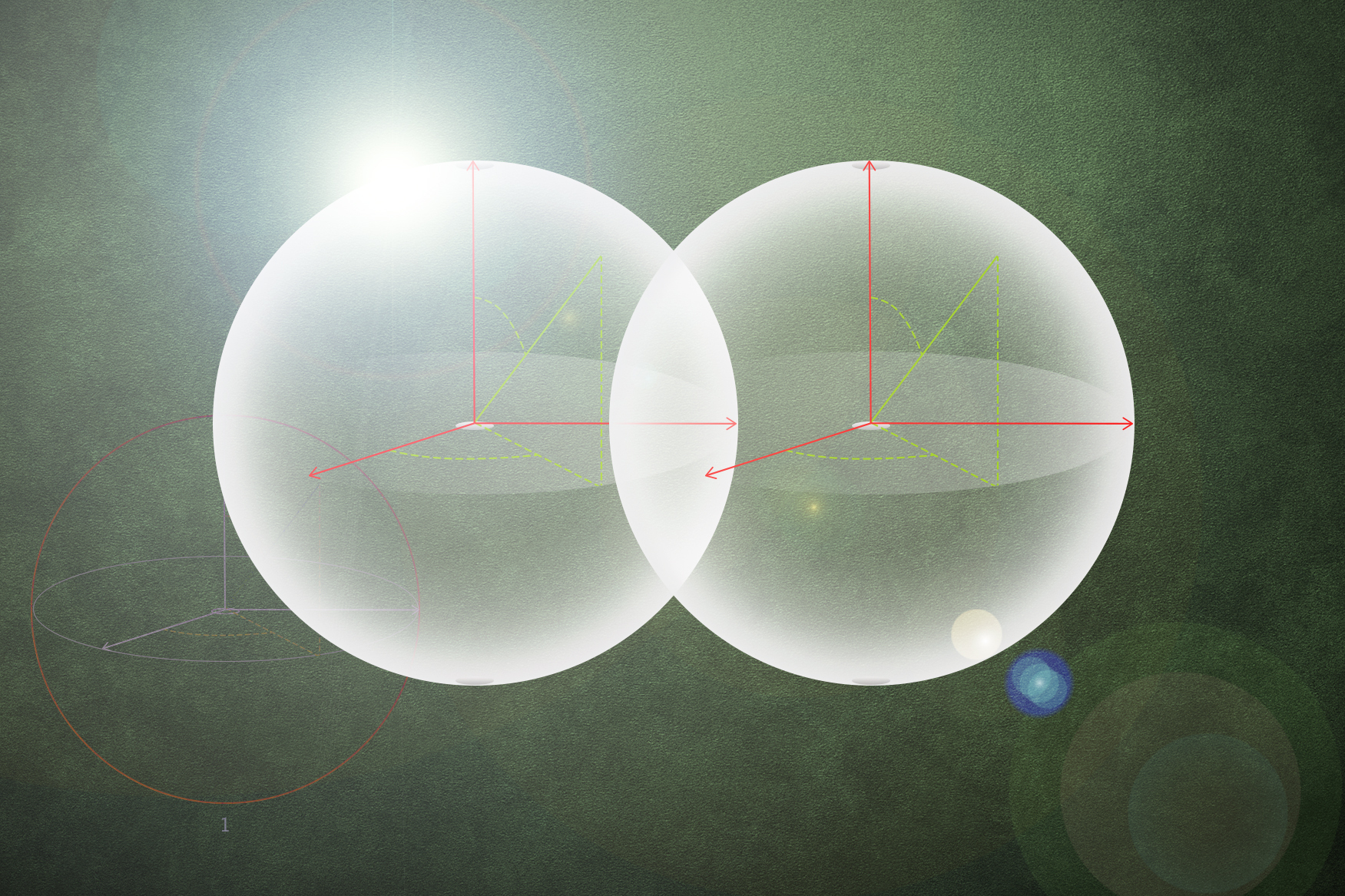

- Denis Auroux, Herchel Smith Professor of Mathematics

- Christina Maranci, Mashtots Professor of Armenian Studies

- Michael Smith, John H. Finley Jr. Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences

- Karen Thornber, Harry Tuchman Levin Professor in Literature and Professor of East Asian Languages and Civilizations

- Yuhua Wang, Ford Foundation Professor of Modern China Studies

“I am delighted to recognize these five outstanding colleagues for their contributions to teaching, mentorship, and research,” Hoekstra said. “Their passion, rigor, and creativity inspire our students every day, giving them the opportunity to ask big questions, explore new ideas, and grow as thinkers and scholars. I am grateful for their extraordinary commitment to our students and our educational mission.”

The Harvard College Professorship was launched in 1997 with a gift from John and Frances Loeb. Professors hold the title for five years and receive support for a research fund, summer salary, or semester of paid leave.

Denis Auroux.

File photo by Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

Illuminating ‘deep connections’ across math

Auroux is a pure mathematician who has spent his career studying ethereal domains such as high-dimensional geometry, in which some shapes are too abstract to be drawn on a blackboard. He finds much more tangible rewards when it comes to teaching.

“I am really happy when I feel that I’ve explained something to a student in a way that suddenly they get it,” Auroux said. “The process of seeing knowledge being acquired, I just love that.”

Auroux has taught at Harvard since 2018. Educated in France, he previously held positions at the Ecole Polytechnique, MIT, and Berkeley. Among his classes is the legendary “Math 55,” a fast-paced course for advanced first-year students.

He described his teaching style as classical — lectures, a “massive amount” of homework, and office hours — and he still prefers an old-fashioned chalkboard. He seeks to guide students toward a deeper understanding of mathematics from multiple perspectives, including algebra, geometry, and analysis. Over the course of the year, the class revisits the same facts from different branches of the discipline.

“There are deep connections that run across different areas of math,” he said. “It’s very beautiful when you get to illuminate that in a class.”

Auroux himself still seeks those deep connections. He studies the geometry of abstract spaces that are not encountered in everyday life, but are subjects of keen interest for mathematicians and theoretical physicists. His research interests include symplectic geometry, low-dimensional topology, and mirror symmetry.

“I’m still trying to understand the same questions I was trying to understand 10 years ago,” said Auroux. “I’m just changing what it means to understand. I have understood certain things, and now I realize there’s more I don’t understand. Maybe mathematicians are a bit obsessive about that.”

Christina Maranci.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Putting images first to promote curiosity

Maranci, an art historian with a focus in pre-modern Armenia, likes to begin her classes with images — perhaps a 7th-century Armenian manuscript depicting the Annunciation, or photographs from fieldwork in Eastern Turkey — and let her students first experience the image, then learn to understand it.

“One of the wonderful things about working with art and visual culture is that you can really confront them with things before they know what they are, and they just look,” Maranci said. “Then you teach them to ask questions about what they’re looking at. For me, it’s a really helpful way of teaching and it also promotes curiosity.”

Maranci’s area of expertise falls at the intersection of art, architecture, and material culture of medieval Armenia. She teaches courses on all aspects of Armenian culture and history, from liturgical textiles to art and literature.

For Maranci, teaching is a “whole-body” experience. She doesn’t read from notes, choosing instead to walk around the room as she lectures, welcoming questions and drawing individual students into lively, public dialogue.

She vividly recalled her own undergraduate struggles — grappling with material that seemed easily understandable to her peers. That experience, she said, informs the way she teaches today.

“I really like to talk them through things,” Maranci said. “I’m putting myself in their shoes and I want to break things down in a way that makes everybody feel that they can learn this stuff. Even when it’s obscure 7th-century Armenian Church architecture, at bottom it’s all knowable, and that’s something I try to get across.”

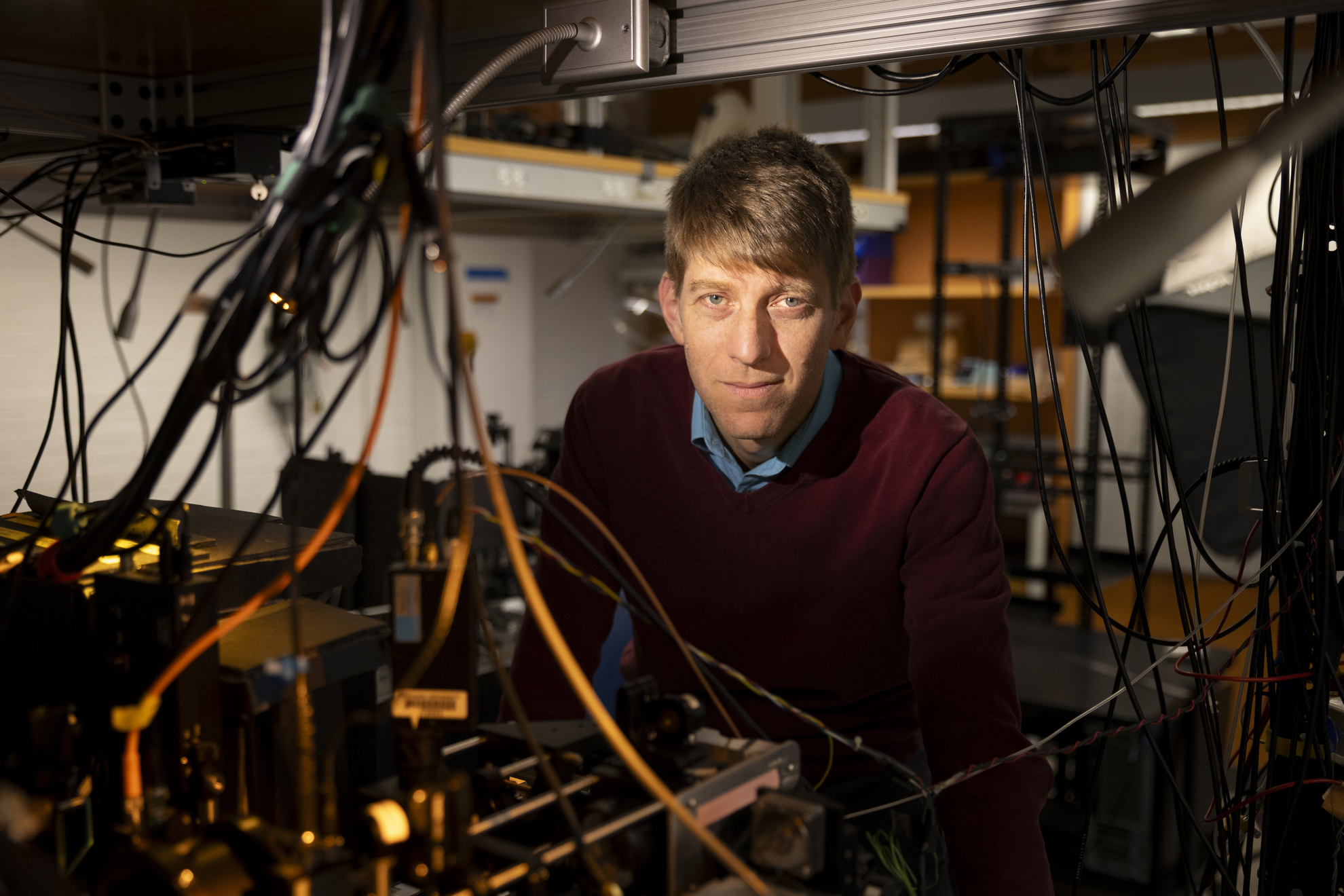

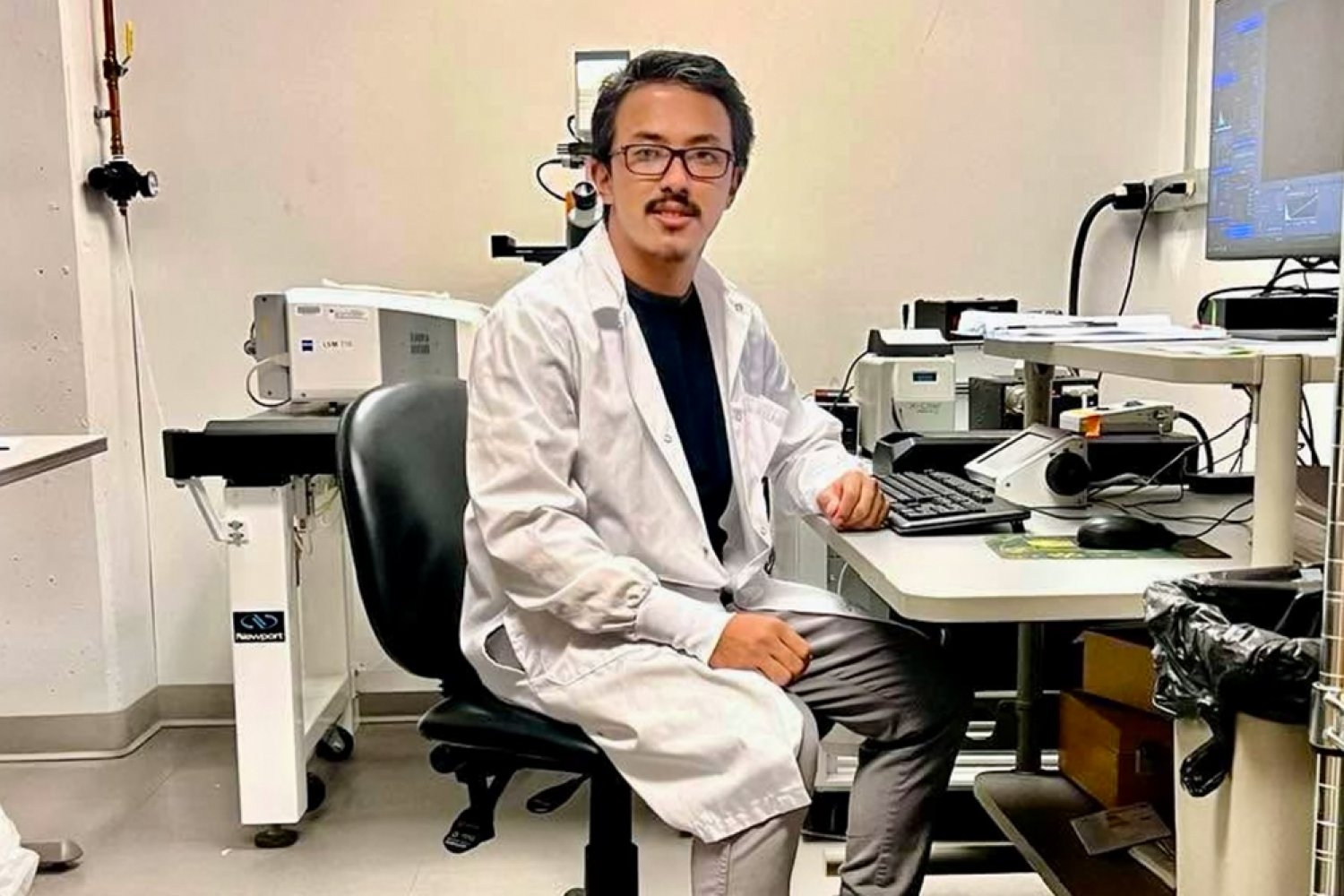

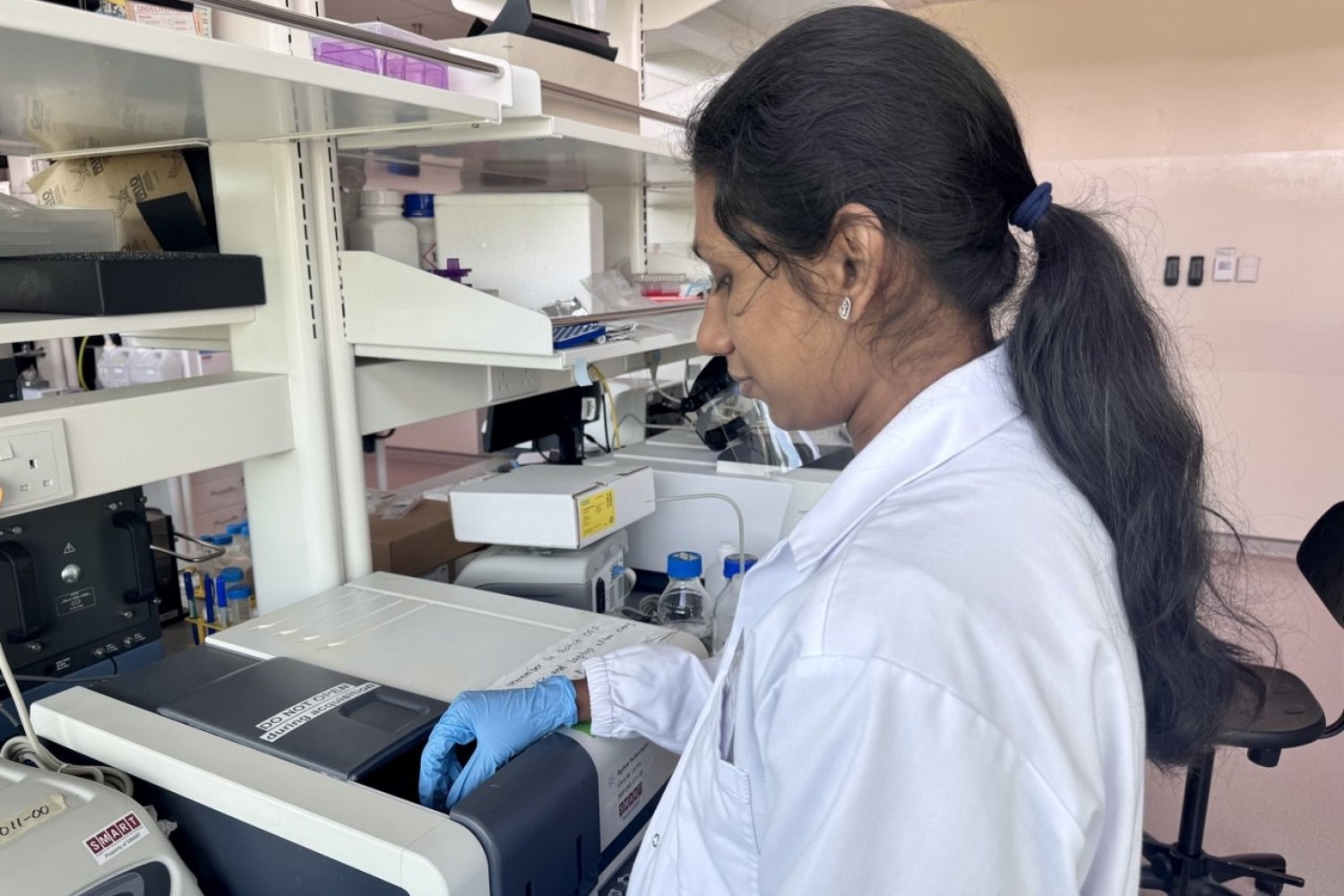

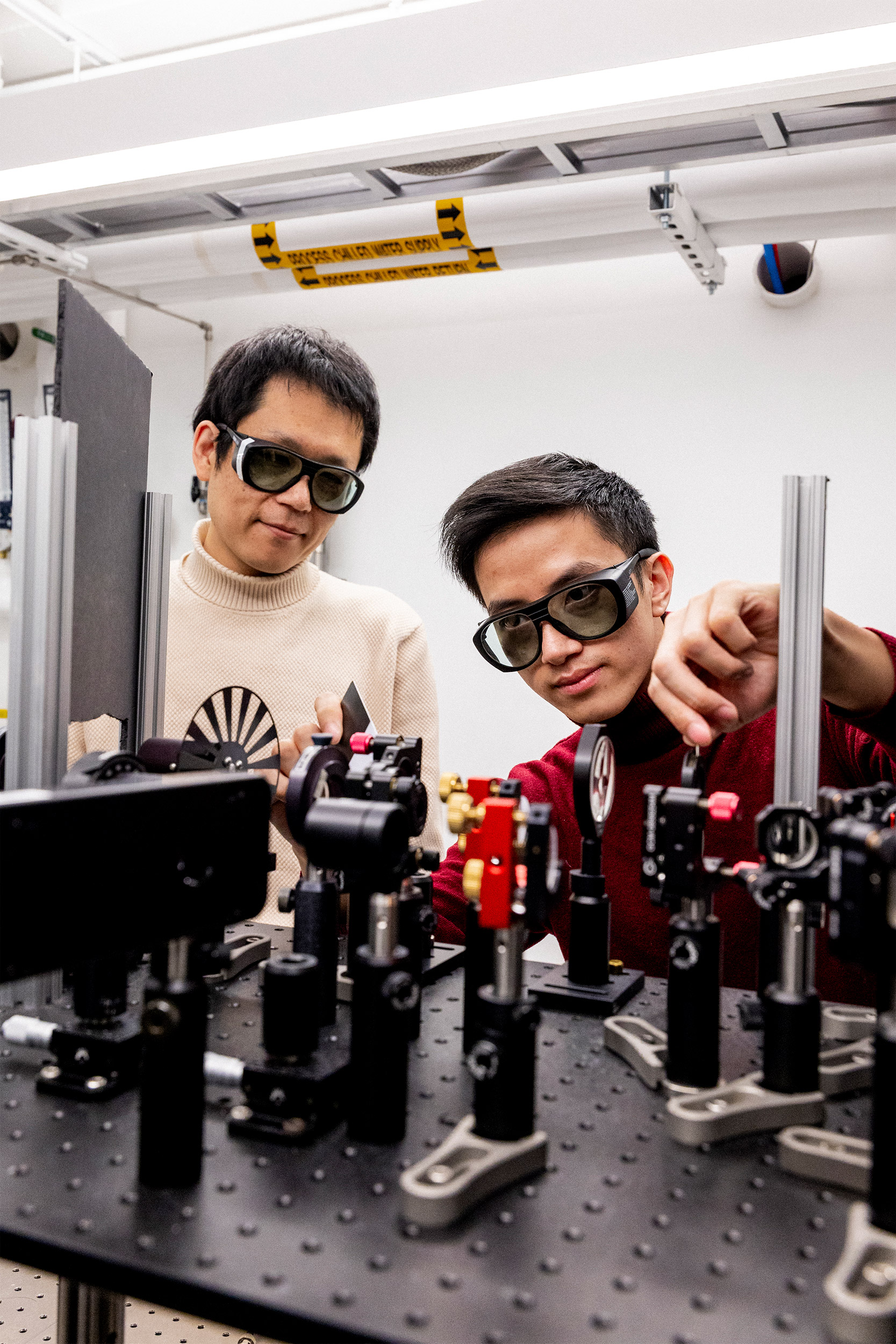

Michael Smith.

Harvard file photo by Grace DuVal

Engaging, hands-on, with problems

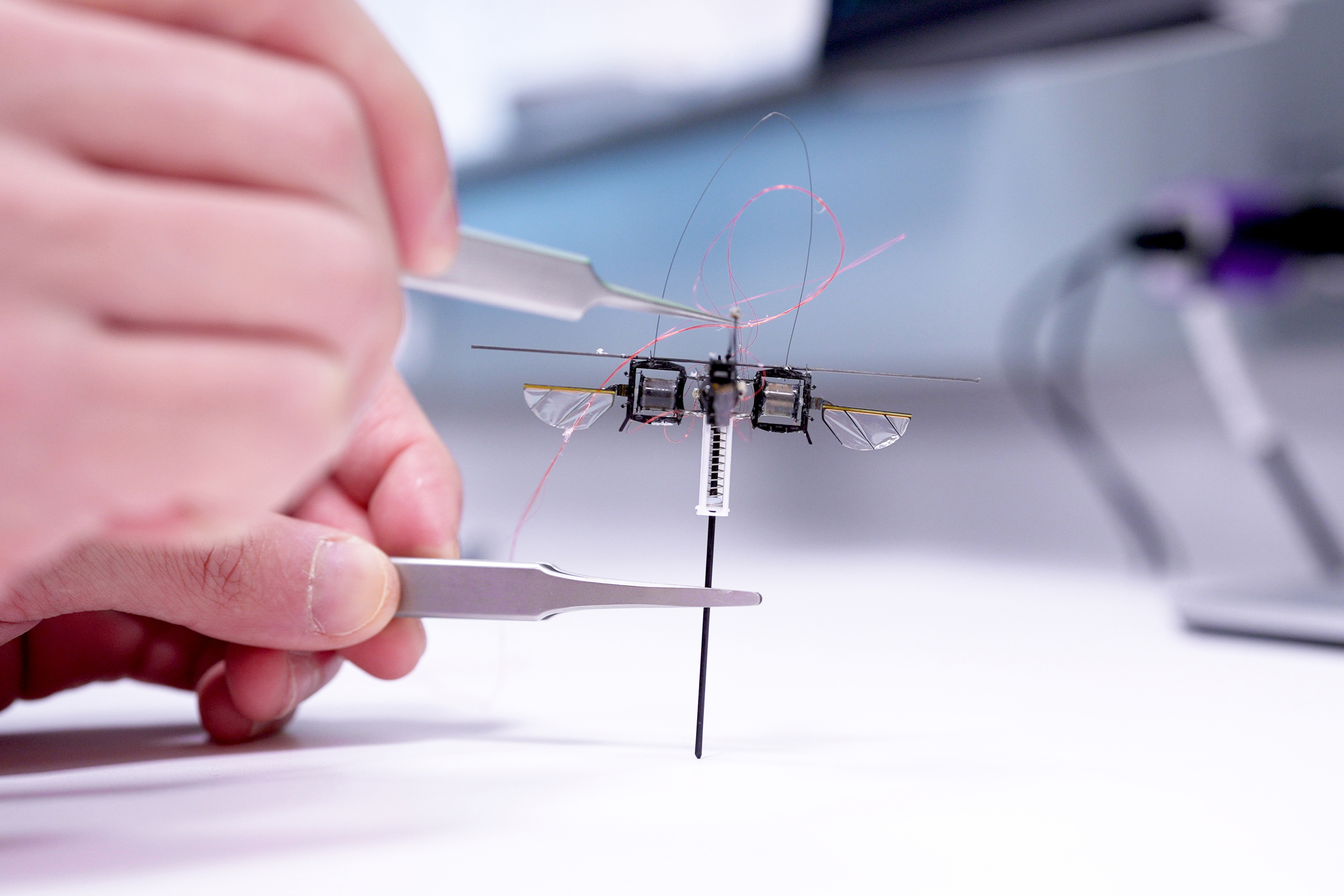

For Smith, the surest route to learning is doing — engaging with real problems, solving technical challenges, and wrestling with ethical dilemmas.

“It’s one of my passions,” he said of teaching. “I especially enjoy working with our undergraduates. I try to make it as hands-on and engaging as possible and connect it to the issues that the students are thinking about at the current time.”

Smith has spent decades thinking about education. He began teaching at Harvard in 1992 and spent 11 years as dean of the FAS. He is writing a book about teaching.

A prime example of his hands-on approach is “CS 32: Computational Thinking and Problem Solving,” an introductory course that enrolls some 300 students. On the first day, students install the Integrated Development Environment (a software interface with tools for computer programmers) on their laptops so they can work on problems simultaneously with the professor. In the final weeks, each student presents an independent project. Some students designed a program to turn the popular online game Wordle into a two-player version; another wrote a program to scrape recipes from the Internet and then suggest what to cook for dinner that night based on the ingredients on hand in the kitchen.

“I want them to have a foundation on which they can start to learn for themselves and become self-sufficient,” said Smith.

He applies a similar philosophy to his upper-level class, “Critical Thinking in Data Science,” in which students grapple with the ethical implications of ever-more-powerful information technologies. The class features two-week “sprints,” exercises in which students build deepfakes and facial recognition programs — and contended with the social consequences of their creations. Smith summed up the dilemma: “Yeah, I can build it, but should I build it?”

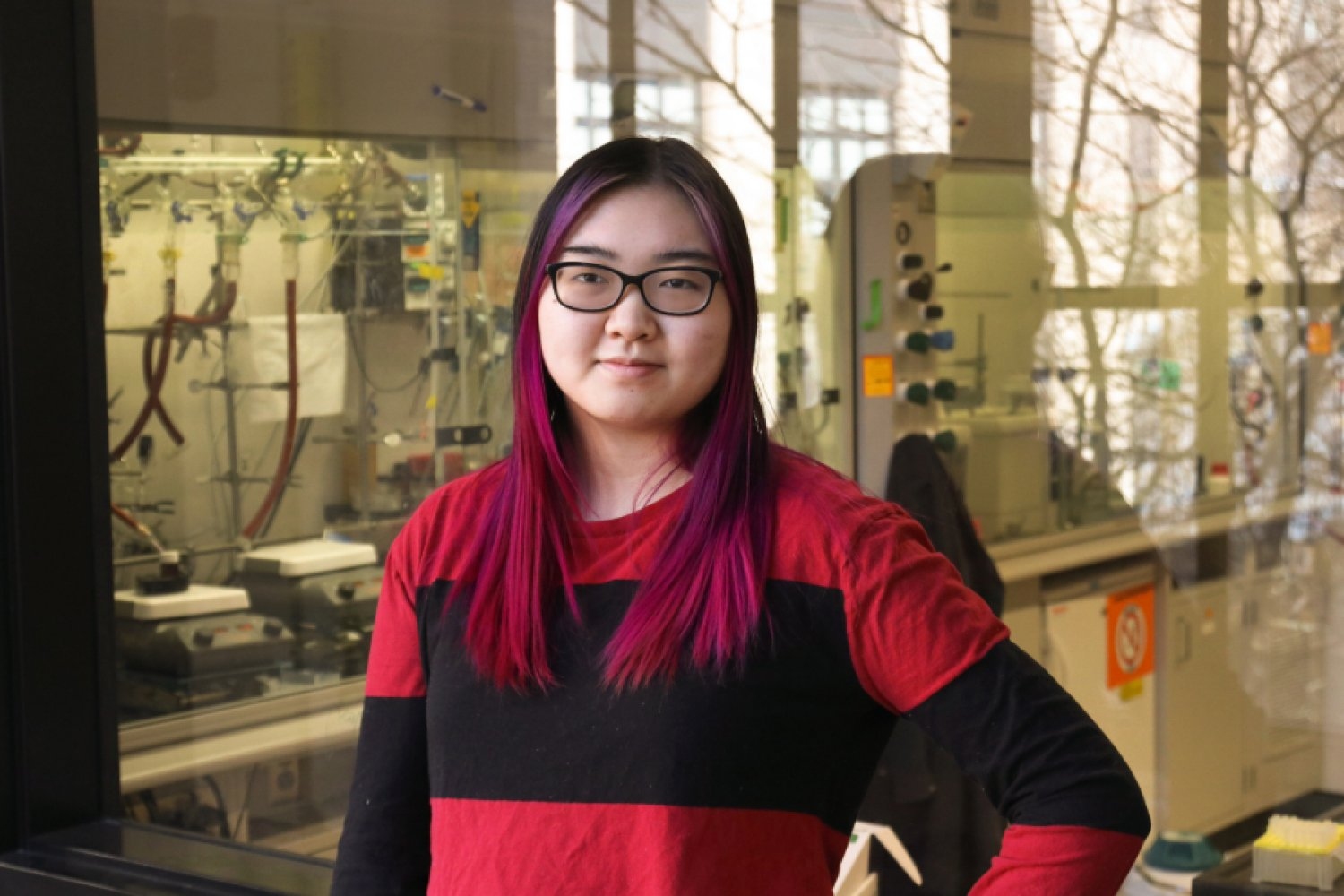

Karen Thornber.

Harvard file photo by Grace DuVal

Creating a space where all perspectives are welcome

Thornber, a cultural historian of East Asia, strives to make her classroom a space where all perspectives are welcome, and where students feel comfortable sharing their insights, even when discussing difficult topics such as gender-based violence, mental health stigmas, or end-of-life care.

Thornber said co-chairing the FAS Civil Discourse Advisory Group and becoming the Richard L. Menschel Faculty Director of the Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning last year made her realize the need to foster this environment with greater intention.

“It’s made me realize the importance of being attentive to students’ own inclination to self-censor, or to come to premature consensus,” Thornber said. “There’s a need for being really intentional about this and being really explicit with the students. If we all come in with the same opinion, that’s great, but we’re going to tackle other opinions as well, because it’s really important that they understand the range of opinions on a difficult topic.”

Thornber’s own scholarship spans the medical and health humanities as well as the environmental humanities, gender justice, indigeneity, and transculturation, as related to the literatures and cultures of East Asia. Her research scope also includes South and Southeast Asia, well as Africa, Europe, and North America. She has taught a range of undergraduate courses, from first-year seminars on gender justice and literature of pandemics to general education courses on mental health and the arts. This fall she will teach a new course, “HUMAN 2: Introduction to the Medical and Health Humanities.”

She said creating a “transformative experience” for students gives her work meaning. For her, that means helping students feel connected to each other and breaking down some of the silos that separate students from different backgrounds so they can all engage in lively and productive classroom discussions.

“I believe very strongly that the humanities provide our students with unique and invaluable information, insights, and perspectives into how we can best make sense of and ameliorate some of our most complex global challenges,” Thornber said. “Not only is it exciting to work with students on increasing their knowledge of global challenges, but also to work with them on how they might ultimately render this knowledge into impactful action. Nurturing the hopefulness, excitement, and creativity that students bring to the table — it’s really a privilege and an honor to be able to do that.”

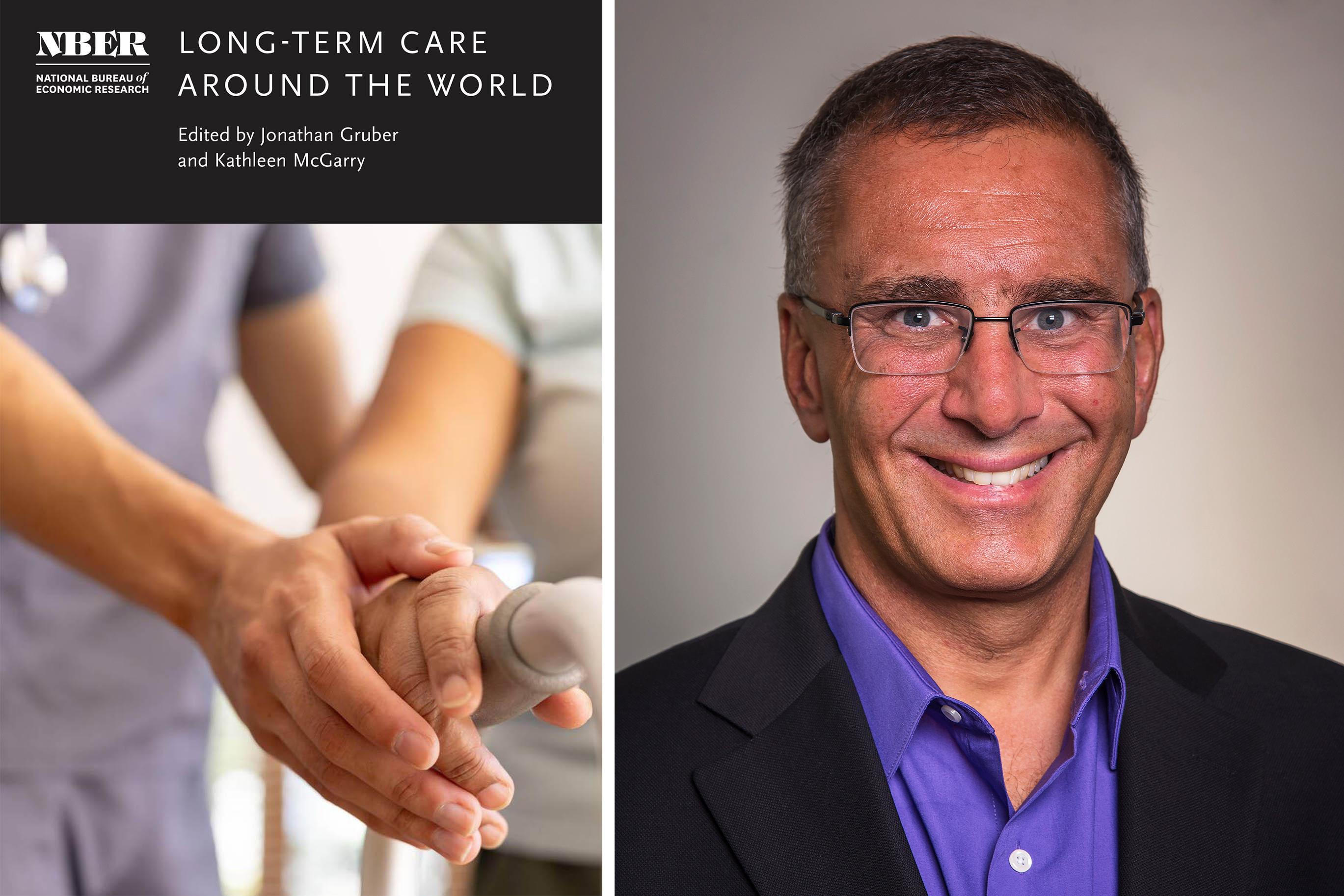

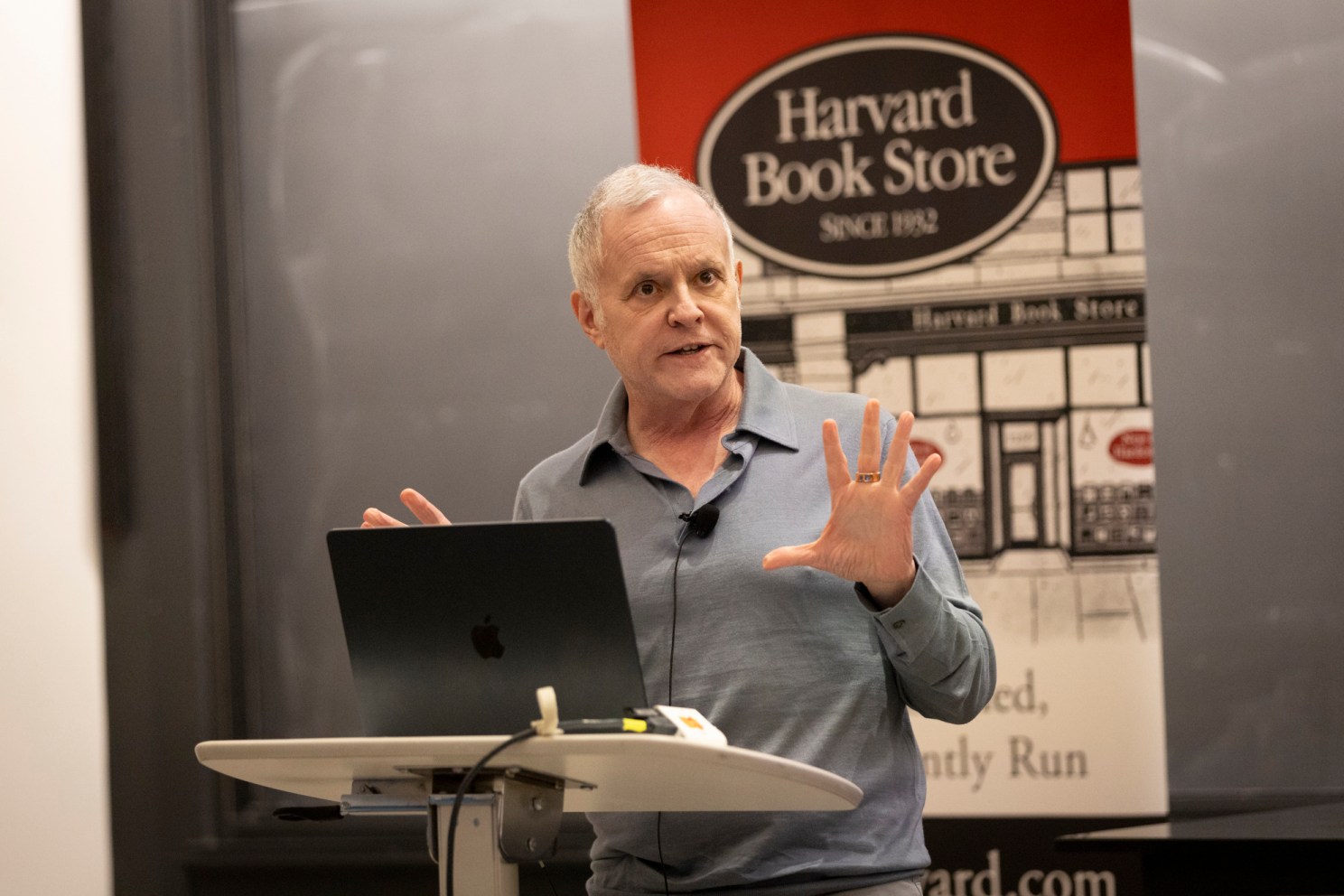

Yuhua Wang.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Learning along with his students

Wang likes to build his political science courses around intellectual debates, to show his students that there is always another way to look at the world. Sometimes this means assigning readings and structuring class discussions to reflect contradictory views.

“I ask them, ‘What do you think?’” Wang explained. “We can challenge the reading and challenge each other. I think that debate form is really useful for getting to the bottom of things. At the end of the conversation, we usually gain more understanding of the issue but also change our previous view about the question.”

Wang’s area of expertise is Chinese politics. He has written extensively about state-building in China from the seventh to 20th centuries and is currently doing comparative research to see how China and Europe diverged politically after the year 1000. The undergraduate courses Wang teaches regularly include “Government and Politics of China” and “Comparative Political Development,” and he is part of a rotation of faculty who teach “Foundations of Comparative Politics.”

Wang said his favorite part of teaching Harvard undergraduates is how often they challenge him intellectually — something that he says is “the best thing that can happen to a professor.” He sometimes presents a provocative argument on purpose, inviting students to push back. More than once, their responses have led him to change his own viewpoint.

“One thing I really want to emphasize to them is I’m learning with them — in this class, we are exploring something together,” Wang said. “I think that’s really important, because I don’t want them to stop learning after this class, or after Harvard. I want them to realize even people my age are still learning, and that I can learn from them.”